By which we mean that many of trade's aggregate benefits may have improved life on average, but proved not to do so for many over the past twenty years.

This is not necessarily a call for the cessation of trade, probably an impossibility in any case, but it does suggest that Pollyanna-ish encomiums to its bracing improvements have to be moderated with a dose of concern and action for the millions whose lot is demonstrably worsened rather than improved. JL

Matthew Klein reports in the Financial Times:

First, free trade may be good overall, but the really interesting questions have to do with the distribution rather than the average. Many Americans have benefited from the decline in the prices of durable goods since 1997 but that came at the cost of underemployment and lower standards of living for millions of their fellow citizens.

Polled in March 2012, top academic economists overwhelmingly agreed that “freer trade improves productive efficiency and offers consumers better choices, and in the long run these gains are much larger than any effects on employment.”

This academic consensus has penetrated popular opinion to the extent that some people believe increasing cross-border trade flows is unambiguously good for everyone. Likewise, there is a relatively common — and wrong — belief that the Hawley-Smoot tariffs were a significant factor in the severity of the GreatDepression .

We don’t want to suggest that trade is bad, but it is worth highlighting that the actual views of the experts who study these issues are much more nuanced than what the “pop internationalists” often spew out.

For example, a newpaper by Daron Acemoglu, David Autor, David Dorn, Gordon H Hanson, and Brendan Price estimates that the sharp increase in bilateral trade between China and the US cost somewhere between 2 and 2.4 million jobs between 1999 and 2011 — about 1 percent of the entire civilian population in 2011. Less than half of those jobs were inmanufacturing sectors that directly competed with Chinese businesses.

We want to focus on the new paper, but not before emphasising that it is just the latestproduct of recent research showing that trade with China, and by extension with other low-wage countries, has cost Americans jobs, increased government spending, and permanently lowered wages for people forced out of well-paying manufacturing employment.

One the earlier studies also found that there has been essentially no net job growth in US industries exposed to international competition since 1990. Instead, most of the net employment gains came from the growth of sectors where it is either impossible to measure productivity (government, healthcare, finance) or where productivity can be estimated and has been found absent (construction).

We certainly don’t wish to ignore the favourable effects of trade: the industrial base that did survive became more productive, while much poorer people on the other side of the world benefited tremendously at the expense of middle-class Americans.

But back to the new paper, whose key innovation is to create a comprehensive measure of the jobs lost as Chinese exports increasingly substituted for American-made products even in sectors completely unrelated to manufacturing.

The authors used two distinct methods and both produced similar estimates.

First, they studied the customers and suppliers of industries affected by Chinese competition:

For example, the chemical and fertilizer mining industry — which is in non-manufacturing — sells 74% of its output to the manufacturing sector. Its largest single manufacturing customer is industrial organic chemicals not elsewhere classified, which accounts for 15% of its sales.This methodology led them to estimate cumulative employment losses of 2.62 million jobs from 1991 through 2011, of which 1.41 million were in manufacturing and 1.22 were in non-manufacturing but related to the manufacturing process. 1.98 million of those 2.62 million jobs were lost in 1999 to 2011, with manufacturing and downstream industries losing about 990,000 jobs each.

Similarly, the iron and ferroalloy ores industry sells 83% of its output to the manufacturing sector, two thirds of which goes to the blast furnace and steel mill industry.

Accordingly, a shock to the demand for a given domestic manufactured good is likely to indirectly impact demand for, and reduce employment in, industries, whether in manufacturing or non-manufacturing, that supply inputs to the affected industry.

[...]

Conversely, a trade shock to the suppliers of a given industry (e.g., the upstream suppliersof tires to the automobile industry) may also affect the industries that are its customers. The direction of this effect is generally ambiguous.

On the one hand, from the perspective of purchasing industries, the trade shock expands input supply and puts downward pressure on input prices, and thus may tend to expand employment in the industries that consume these inputs… On the other hand, the trade shock may destroy existing long-term relationships for specialized inputs as domestic inputsuppliers are driven out of business, creating a force towards contraction in the industries that were their customers.

The second estimate was an attempt to consider the welfare of unrelated sectors of the economy that were particularly affected by China-induced de-industrialisation because of local employment effects. When the town steel mill shuts down, the neighborhood bar has trouble staying open, for example.

The economists did this by sorting mainland America’s 722 commuting zones according to how exposed their local economies were to low-cost manufacturing competition, either directly or because of the effects on downstream suppliers noted above.

They then divided employment into three basic categories: tradable sectors threatened by Chinese competition, tradable sectors that were isolated from Chinese competition (everything from farming to aerospace), and non-tradable sectors. The theory is that the tradable sectors ought to respond mostly to national and global economic conditions while the non-tradable sectors — hairdressers, restaurants, doctors, etc — are sensitive to local conditions.

(If this methodology sounds familiar, it is because they based it on the work done by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi to determine the impact of household indebtedness and asset price declines.)

In 1991, the tradable sector exposed to Chinese competition accounted for 20.2 per cent of US employment, the isolated tradable sector (mostly high-end manufacturing industries) accounted for 6.7 per cent of US employment, and the remaining 73.1 per cent of jobs were in non-tradable sectors.

Surprisingly, the economists were not able to find much of an impact on local employment in non-tradable sectors, although they did show that many of the people who lost their jobs in industries vulnerable to Chinese competition were unable to find new jobs elsewhere — a finding that fits with other things we know about the ability of downsized men to remain in the workforce:

These estimates suggest that employment gains through the sectoral reallocation effect are largely offset by negative aggregate demand effects…While our estimates suggest the presence of strong aggregate demand effects that limit employment gains in the non-exposed sectors of trade-exposed local labor markets, we would anticipate these local demand effects primarily impact employment in the non-traded sector rather than the non-exposed tradable sector.Despite this, they still think that a comprehensive accounting of the negative impact of Chinese trade competition would be even bigger than their input-output based estimate:

Our results however provide scant evidence for differential employment impacts in the two non-exposed sectors.

Had import competition from China not increased after 1999, trade-exposed industries in local labor markets would have avoided the loss of 2.35 million jobs…The fact that employment effects on exposed industries in CZs are slightly larger than the direct and indirect effects of import competition in national industries is suggestive of negative local aggregate demand spillovers.We see three takeaways.

Such spillovers imply that [Keynesian] multipliers operating at the local level suppress demand in non-exposed industries as well, inducing further employment declines in trade-exposed industries.

[...]

Combining figures from exposed and non-exposed industries, the overall local impact is 2.37 million jobs whose loss would have been averted absent further increases in Chinese import competition after 1999…This estimate is a lower bound on the aggregate total impact of increased import competition from China on national employment.

First, free trade may be good overall, but as with most questions in economics, the really interesting questions have to do with the distribution rather than the average result. Many Americans have benefited from the slow and steady decline in the prices of durable goods since 1997 but that came at the cost of underemployment and lower standards of living for millions of their fellow citizens.

The ideal outcome would have been for the government to ease the suffering imposed on those who lost their jobs by taxing everyone else who saved so much money on their toys and gadgets, but there are many reasons why that was politically difficult. For example, the pop internationalists blunt the pressure to help because they claim it is easy to switch jobs and that unimpeded flows of goods and services have no downside.

Second, as the economists imply in their paper, there were other significant costs associated with the Chinese import penetration.

US employment growth, while significantly worse than it otherwise would have been, was also surprisingly stronger than the economists would have predicted because domestic demand for services and housing partly — and only temporarily — offset the widening gulf between imports and exports.

That demand was made possible by excessive household borrowing, which is why Dan Davies convincingly argued that much of what we think of as “secular stagnation” was really just the inevitable consequence of embracing free trade while relying on monetary policy to sustain total spending.

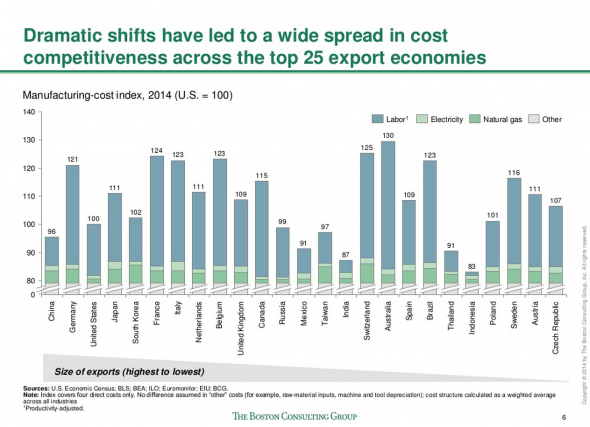

The final takeaway is more positive: the era of massive job losses induced by trade with China may be coming to a close. Thanks to a combination of wage inflation and slowing productivity growth in China, combined with the shale boom and lower transit costs to get products to the domestic market, US manufacturers are now about as competitive as Chinese ones, according to the Boston Consulting Group:

Tellingly, the US’s yawning bilateral trade deficit with China (in goods only) seems to have stopped growing since 2012. The negative impact of globalization may soon end, if hasn’t ended already.

Now all we need to worry about are the machines.

0 comments:

Post a Comment