The question is whether this is merely prudent investment philosophy at a time of uncertainty, or the sacrifice of higher future value from innovation in favor of lower short-term assurance. JL

Victor Basta reports in Venture Beat:

Capital is flowing into funds of all types, yet the rate of investment is shrinking rapidly. This could mark the decline of true venture capital as they are forced to evolve into private hedge funds or momentum investors, investing far larger amounts in much later stage pre-IPO companies, and drifting further away from taking higher risk, long-term investment in innovation. While value is up, that is mainly due to larger rounds for more established companies, not true venture capital.

We are in a perverse moment in the global venture capital industry: VCs are fast coming to resemble private hedge funds, and the more money they are able to raise, the worse off startups are becoming.

Capital is flowing into funds of all types, yet the rate of investment is shrinking rapidly. This could mark the decline of true venture capital by many funds as they are forced to evolve into private hedge funds or momentum investors, investing far larger amounts in much later stage pre-IPO companies, and drifting further away from taking higher risk, long-term investment in innovation. Perversely, this risk is greatest for the most valuable, value-adding investors with the best track records, since they can raise the most money.

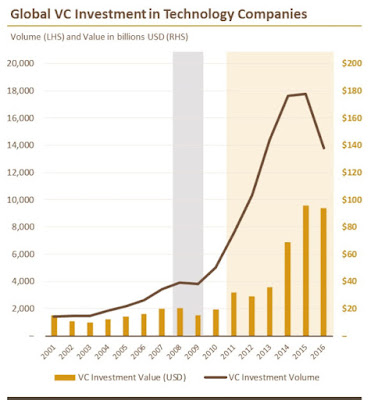

Activity is down

U.S. venture capital activity was essentially flat in Q1 after a sharp drop over the past two years, PwC and CB Insights have reported. While value is up 15 percent, that is mainly due to larger rounds for more established companies, not true venture capital. However, this does nothing to change the macro picture, which is trending down:

Record amounts of capital flowing to VC funds

At the same time, the last five quarters have been nearly the best ever for raising venture funds. Almost $50 billion in new venture funds has been raised since the start of 2016 ($40 billion in 2016, another $9 billion in Q1 2017), and the tide shows no sign of turning. This is by far the strongest fundraising period since the heady days of the 2000 tech bubble.

So the obvious question is, where will VCs invest their hard-won war chests, especially since the overall trend in number of deals is down?

VCs pushed to become private hedge funds

My view is that the VC industry is evolving into a private hedge fund industry, raising larger funds and investing larger amounts in late stage companies that are well past the innovation stage. While very few of the best funds have the discipline to keep their fund sizes artificially down (at different times, both Sequoia and Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers took less money than investors offered), the vast majority of funds raise as much as they can.

One example of this trend is Index Ventures, the U.S. and European reference VC that has been a key investor in several high-value companies, from Dropbox to Skype to Just Eat. Below is the trend line of its fund sizes:

Realistically, a “venture” fund nearing $600 million in size is already beyond the limit of being able to make real venture stage investments. Why?

- Very few funds (Sequoia, Andreessen Horowitz, Kleiner, and a few others) get to invest early in the highest value companies. Among CNBC’s 2015 Disruptor 50 list, Kleiner alone was an investor in 15. On CB Insights’ list of unicorns, only three venture firms feature in the most active group (the rest are late stage investors). Any venture firm NOT in the top group doesn’t have the opportunity to invest early enough in high-value companies to deploy a large $500-700 million venture fund successfully.

- Companies generally need less money to scale now compared to a decade ago: AWS, cloud software, app stores, and development in low-cost markets have cut the cost of scaling a business by 50 percent or more vs. 10 years ago. For example, Facebook only had 3,200 staff when it IPO’d for $100 billion. Less capital needed equals less venture money required.

This trend won’t end funding for startups overnight. If only a quarter or a third of a fund is effectively a private hedge fund, there will be room to accommodate a large number of more capital-efficient startups. But if the majority of a fund goes to late stage “momentum rounds” that perform reasonably well, VCs will care a lot less about venture in future.

- Finally, there is now a ready market for large late-stage rounds. Many companies are staying private much longer and raising “mega rounds” before IPOing (witness AirBnB’s $1 billion round in Q1 2017). An unfortunate side effect of these mega rounds is that, as funds become driven by larger momentum investments, less interest and attention is paid to “ordinary” venture investments going to the potential unicorns of the future.

The bottom line: The more money VCs are able to raise, the worse it is for startups.

0 comments:

Post a Comment