Ernie Smith reports in Motherboard:

Franklin claimed software programs were not subject to copyright, because the operating system software was utilitarian, not expressive. Apple sued. An appeals court created case law called Apple Computer, Inc. v. Franklin Computer Corp. that allowed software to be copyrighted. Apple actually lost the first round in a lower court. That legal decision helped to redefine our relationship with computer software, by ensuring that copyright laws made for the pre-digital era would still matter even when paper wasn't the medium.

The Apple II computer didn’t attract as many clones as the IBM PC, but the clone-makers the machine did attract often had pretty interesting second acts.Often, retrospectives on computer history focus on the IBM PC era and how that system's many clones helped to democratize computing by centering most computing-industry efforts on a single platform—a major breakthrough at the time. But other platforms attracted clones as well, including the Apple II.

Certainly, Apple was small enough early on that it had to occasionally cut some deals with some third parties to support its budding platform.

In 1979 for example, Bell & Howell, a company better known for classroom projectors than computers, released one of the only authorized clones of the Apple II in the United States. Around 10,000 units of the machine were produced, in a successful, early attempt to bring the Apple II into schools.

The Bell & Howell machines were interesting in that they were completely black, meaning Apple's partner was making more stylish computers than Apple was for a time.

It was nearly 20 years before Apple allowed for another company to resell clones of its machines. But that didn't stop unauthorized clone-makers from trying to do the same thing, though the computing giant's protectionist habits kicked in quickly.

And oddly enough, it may have the best thing for everyone involved—including consumers.

How a company named Franklin blatantly ripped off Apple and set a legal precedent in the process

Is a piece of software copyrighted if it's not printed out and is buried inside of a machine? This sounds like an obvious question—yes, of course it is—but it wasn't a question that had been asked before in a court of law.

Surprisingly, it wasn't a PC clone-maker that forced the question, but one making Apple II machines.

Franklin Computer Corporation, a New Jersey firm, spent the early 80s making Apple II clones that were close feature-wise to the original machines. The company talked a big game, too.

"The Franklin ACE 100—a professional personal computer with the quality and reliability for the most demanding business applications," the firm stated in a 1982 ad. "It is sweeter than an Apple."

The reason why it worked so well had much to do with the way that Franklin copied the hardware and software necessary for the ACE 100: The company did so wholesale, directly copying the hardware and software of the Apple II in an obvious way, while adding only a handful of minor additional features, such as the ability to create lower-case letters, which the Apple II platform didn't initially support.

In the case of the software in particular, the copying was so blatant that Franklin essentially admitted doing so, claiming it would be infeasible for the company to reverse-engineer its own version of the Apple ROM software. Further, Franklin claimed that it didn't need to anyway, because software programs are not subject to copyright, because the operating system software was utilitarian in nature, not expressive.

It was a weird legal argument, one that allowed Franklin to make tens of millions of dollars off of an Apple knockoff using Apple's own software. But it was one that took advantage of the fact that there was a gap in case law around this specific issue at the time. Understandably, Apple sued, unhappy about the precedent that it set.

Even Steve Wozniak, generally a fan of efforts at compatibility and someone known for sharing the technical details of his work, spoke out in the press about the blatant nature of Franklin's theft.

"It's just a total copy," Wozniak told InfoWorld in August of 1982. "If anyone at Apple did something like that, we'd try to put them in jail."

A year later, an appeals court decisively agreed with Wozniak, creating an oft-cited piece of case law called Apple Computer, Inc. v. Franklin Computer Corp. that allowed software to be copyrighted in all cases. Apple actually lost the first round in a lower court, but the appeals court ruling was pretty hard to ignore.

A January 1984 analysis of the case in the Golden Gate University Law Review points out that the legal decision helped to redefine our relationship with computer software, by ensuring that copyright laws made for the pre-digital era would still matter even when paper wasn't the original medium.

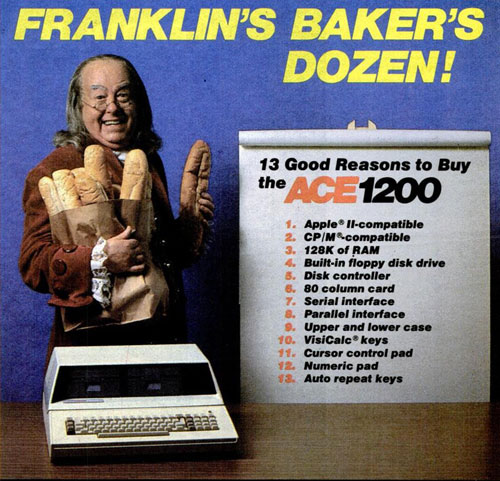

The Third Circuit's decision in Apple Computer, Inc. v. Franklin Computer Corporation is significant because it held that all computer programs, whether expressed in object code embedded in ROM or expressed as an operating program, are copyrightable subject matter. Thus, by granting copyright protection to all programs, the Franklin opinion has helped stabilize copyright law in relation to computer software and has allowed copyright to become the most effective, most easily obtainable, and most preferred form of legal protection· for computer programs.And while Franklin Computer eventually cut a deal with Apple, it was not forced to immediately stop selling its machines, a partial victory in its own right, and one that gave the company time to comply with the order."I know, let's get a Ben Franklin lookalike to hold six loaves of bread while standing behind a computer and call it a baker's dozen. Makes total sense." Image: InfoWorld/Google

By 1986, however, around the time Franklin had legitimately started reverse-engineering products, Apple's legal pressure forced Franklin out of the PC market for good.

Unfortunately for Apple, another competitor had figured out how to clone its Apple II platform the right way.

That competitor, VTech, had built a computer called the Laser 128 that sported a 99.8 percent level of compatibility with the Apple IIc Plus, according to Old-Computers.com.

The Laser 128 was a hugely successful machine for what it was, and one that was legitimately reverse engineered in a clean-room environment, allowing the company to remain active on the market throughout the late 80s, despite Apple's attempts to sue.

The machine even sold at Sears, to the detriment of the Commodore 128.

But the Apple II, obviously, didn't stick around forever. The incompatible Macintosh platform was the future of Apple as a company, and the IBM PC was simply the industry's future from a clone standpoint.

So where did it leave these companies to go next?

Why the eventual demise of the Apple II clone market was a good thing for consumer electronics

What's interesting to me about both Franklin and VTech is that their respective experiences in the Apple clone space each proved informative to their later success stories on the general consumer market.

(There were other clone-makers for the Apple II, of course, but these two companies have perhaps the most fascinating story arcs.)

Around the same time, each company moved away from Apple II clones and made a play for commodity electronics. While cloning a larger company's computers made for a great way to get their feet wet in the computer industry, both Franklin (formed in 1981) and VTech (formed in 1976) were soon ready to do something more interesting.

In the case of VTech, that more interesting thing first came in the form of Socrates. The NES-style educational system, which it first released in 1988, proved a turning point for the company, which had dabbled in consumer electronics periodically in the 80s but fully committed to them around this time. While it still produced computers until 1997, the Hong Kong-based company's future actually laid with the consumer market. (There's a lineage between Apple II clones and the DigiArt Creative Easel, clearly.)

Another major win for VTech came in 1991, when the company, aware of the Federal Communications Commission's recent decisions opening up spectrum originally used for television signals, created what turned out to be the first digital cordless phone on

the 900 MHz frequency. To this day, VTech is a leader in both the cordless phone and educational toy markets, despite the fact that the two markets seemingly have very little in common.

Meanwhile, Franklin, which was forced to diversify due to legal pressure from Apple and challenges from bankruptcy, found a niche it could work within by embracing the handheld computing market.

The idea, per the Associated Press, went like this: Rather than accepting the idea that households would rely on one large computer, they instead pushed toward the market of numerous smaller ones. There were other companies that were hitting this niche, like Tiger Electronics, but they were focused on games.

Franklin, instead, created more useful tools, starting in December of 1986 with the Spelling Ace, a small computer in which you could type in a word, and the machine would let you know the correct spelling.

It was a simple but powerful idea, and it led to lots of similar handheld computers from Franklin over the next two decades, including translators and handheld dictionaries.

"This is sort of the Cabbage Patch of 1987. We haven't been able to build them fast enough," Franklin Executive Vice President Michael Strange told the AP in early 1988 after a successful 1987 holiday season.

This eventually took Franklin into some interesting directions, including the creation of a PCMCIA-sized personal assistant called the Rex in 1997. It was a clever concept, but as CNET notes, the need to fit inside a tiny PC Card slot ultimately made the device impossible to improve. (Apple knows a thing or two about that kind of situation.)

More colorfully, Franklin forged a sponsorship deal with Johnny Cash, having the Man in Black recite his favorite Bible passages in audio form. While the company sold the recitations in CD and cassette form as a way to promote its electronic bibles, the firm also found a way to integrate Johnny Cash's voice with technology.

"Working on this new product with the good people at Franklin has been a great source of inspiration for me and my family," Cash said in 1999.

Granted, neither VTech and Franklin ended up becoming Dell. In fact, both companies aren't doing so hot these days. After a few mergers, Franklin's website currently looks like this. And while VTech remains a company, it has become known more for hacking than hit toys.

In a way, though, the fact that the Apple II clone market proved a dead end for both companies was good for consumers as a whole. Our digital lifestyles needed innovations both big and small—especially in the pre-smartphone era.

Of the many interesting footnotes about the Apple II's clone competition, perhaps the most interesting is the fact that in 1987, the fates of Franklin and VTech briefly coincided in a legal battle.

Franklin argued that VTech's Laser 128 was damaging the sales of its own clones, and that the Laser 128 was using software it owned the copyright to.

Central Point, the vendor that worked with both companies, denied Franklin's allegations.

"The software in the Laser 128 is not at all the same as the software we sold to Franklin in 1984," Central Point President Michael Brown told the Philadelphia Inquirer at the time. "We feel they're doing this as a rather unethical attempt to block the 128, which was out many months before their machine, to provide them a competitive advantage."

As the article notes, Franklin wouldn't have had a case at all had it not been accused of doing the exact same thing five years earlier, creating a legal precedent for software copyright.

Oh, the irony.

0 comments:

Post a Comment