Suing Travis Kalanick might have been intended to preserve that value, but the reputational cost may be hard to overcome. JL

Ben Thompson reports in Stratechery:

There may be short-term gain in screwing over a founder or bailing on a floundering company, but it simply is not worth it in the long-run: word will spread, and a venture capitalists’ deal flow is only as good as their reputation. Uber’s most recent valuation of $68.5 billion nearly matches the worth of every successful Benchmark-funded startup since 2007. Whatever outcome results from this mess will be a suboptimal one.

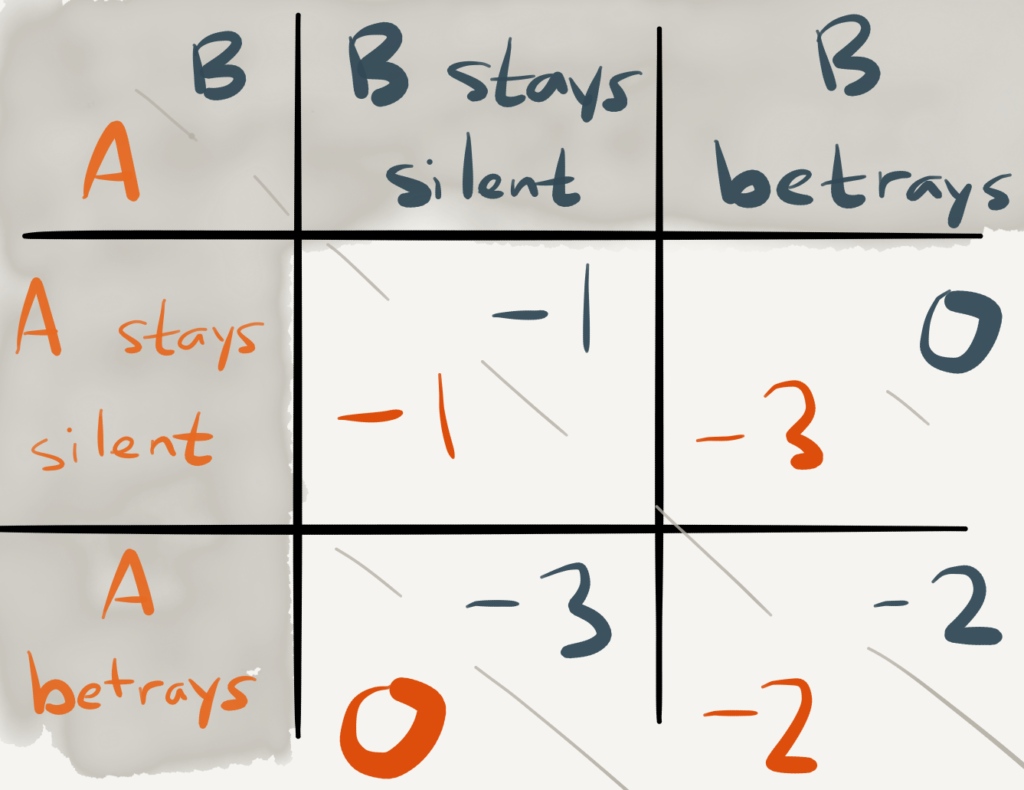

By far the most well-known “game” in game theory is the Prisoners’ Dilemma. Albert Tucker, who formalized the game and gave it its name in 1950, described it as such:

Two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of communicating with the other. The prosecutors lack sufficient evidence to convict the pair on the principal charge. They hope to get both sentenced to a year in prison on a lesser charge. Simultaneously, the prosecutors offer each prisoner a bargain. Each prisoner is given the opportunity either to: betray the other by testifying that the other committed the crime, or to cooperate with the other by remaining silent. The offer is:The dilemma is normally presented in a payoff matrix like the following:

- If A and B each betray the other, each of them serves 2 years in prison

- If A betrays B but B remains silent, A will be set free and B will serve 3 years in prison (and vice versa)

- If A and B both remain silent, both of them will only serve 1 year in prison (on the lesser charge)

What makes the Prisoners’ Dilemma so fascinating is that the result of both prisoners behaving rationally — that is betraying the other, which always leads to a better outcome for the individual — is a worse outcome overall: two years in prison instead of only one (had both prisoners behaved irrationally and stayed silent). To put it in more technical terms, mutual betrayal is the only Nash equilibrium: once both prisoners realize that betrayal is the optimal individual strategy, there is no gain to unilaterally changing it.

TIT FOR TAT

What, though, if you played the game multiple times in a row, with full memory of what had occurred previously (this is known as an iterated game)? To test what would happen, Robert Axelrod set up a tournament and invited fourteen game theorists to submit computer programs with the algorithm of their choice; Axelrod described the winner in The Evolution of Cooperation:

TIT FOR TAT, submitted by Professor Anatol Rapoport of the University of Toronto, won the tournament. This was the simplest of all submitted programs and it turned out to be the best! TIT FOR TAT, of course, starts with a cooperative choice, and thereafter does what the other player did on the previous move…This is the exact opposite outcome of a single-shot Prisoners’ Dilemma, where the rational strategy is to be mean; when you’re playing for the long run it is better to be nice — you’ll make up any short-term losses with long-term gains.

Analysis of the results showed that neither the discipline of the author, the brevity of the program—nor its length—accounts for a rule’s relative success…Surprisingly, there is a single property which distinguishes the relatively high-scoring entries from the relatively low-scoring entries. This is the property of being nice, which is to say never being the first to defect.

Silicon Valley’s Iterated Game

What happens in Silicon Valley is far more complex than what can be described in a simple game of Prisoners’ Dilemma: instead of two actors, there are millions, and “games” are witnessed by even more. That, though, accentuates the degree to which Silicon Valley as a whole is an iterated game writ large: sure, short-term outcomes matter, but long-term outcomes matter most of all.

That, for example, is why few folks are willing to criticize their colleagues or former companies: today’s former co-worker or former manager is tomorrow’s angel investor or job reference, and memories are long and reputations longer.

That holds particularly true for venture capitalists: as Marc Andreessen told Barry Ritholtz on a recent podcast, “We make our money on the [startups] that work and we make our reputation on the ones that don’t.”

Note the use of plurals: a venture capitalist will invest in tens if not hundreds of companies over their career, while most founders will only ever start one company; that means that for the venture capitalist investing is an iterated game. Sure, there may be short-term gain in screwing over a founder or bailing on a floundering company, but it simply is not worth it in the long-run: word will spread, and a venture capitalists’ deal flow is only as good as their reputation.

The most famous example of this is cemented in Valley lore. From The Facebook Effect:

Facebook’s success was beginning to make waves. And in Silicon Valley, success attracts money. More and more investors were calling. Zuckerberg was uninterested. One of the supplicants was Sequoia Capital. Among the bluest of blue chip VCs, Sequoia had funded a string of giants—Apple, Cisco, Google, Oracle, PayPal, Yahoo, and YouTube, among many others. The firm is known in the Valley for a certain humorlessness and a willingness to play hardball. Sequoia eminence grise and consummate power player Michael Moritz had been on Plaxo’s board and was well acquainted with Sean Parker. It was not a mutual admiration society. Parker saw Moritz as having contributed to his downfall. [Parker was fired from the company he founded by the board, including Moritz] “There was no way we were ever going to take money from Sequoia, given what they’d done to me,” says Parker.Plaxo raised a total of $19.3 million in the rounds in which Sequoia participated; was whatever percentage of that $19.3 million Sequoia put in worth missing out on the chance to invest in one of the greatest grand slams in the history of venture investing?

The entire point of venture investing is to hit grand slams, and that calls for more swings of the bat. After all, the most a venture capitalist might lose on a deal — beyond time and opportunity cost, of course — is however much they invested; the downside is capped. Potential returns, though, can be many multiples of that investment. That is why, particularly as capital has flooded the Valley over the last decade, preserving the chance to make grand slam investments has been paramount. No venture capitalist wants to repeat Sequoia’s mistake: better to be “nice”, or, as they say in the Valley, “founder friendly.”

Benchmark Sues Kalanick

This is why what happened last week was so shocking: the venture capital firm Benchmark Capital filed suit against former Uber CEO Travis Kalanick for fraud, break of contract, and breach of fiduciary duty. From Axios:

The suit revolves around the June 2016 decision to expand the size of Uber’s board of voting directors from eight to 11, with Kalanick having the sole right to designate those seats. Kalanick would later name himself to one of those seats following his resignation, since his prior board seat was reserved for the company’s CEO. The other two seats remain unfilled. Benchmark argues that it never would have granted Kalanick those three extra seats had it known about his “gross mismanagement and other misconduct at Uber” — which Benchmark claims included “pervasive gender discrimination and sexual harassment,” and the existence of confidential findings (a.k.a. The Stroz Report) that recently-acquired self-driving startup Otto had “allegedly harbored trade secrets stolen from a competitor.” Benchmark argues that this alleged nondisclosure of material information invalidates Benchmark’s vote to enlarge the board.Giving three extra seats on the board to the CEO was certainly founder friendly; that the expansion happened at the same time Uber accepted a $3.5 billion investment from Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, which came with a board seat, suggests Benchmark viewed the board expansion as a way to protect its own interests and influence as well. After all, longtime Benchmark general partner and Uber board member Bill Gurley had been pursuing ride-sharing years before Uber came along, and the investor had penned multiple essays on his widely-read blog defending and extolling Kalanick and company.

Moreover, Benchmark alleges that Kalanick pledged in writing — as part of his resignation agreement — that the two empty board seats would be independent and subject to approval by the entire board (something Benchmark says was the reason it didn’t sue for fraud at the time). But, according to the complaint, Kalanick has not been willing to codify those changes via an amended voting agreement.

Then again, by June 2016, when the board was expanded and the Saudi investment was announced, Gurley’s posts had taken a much sterner tone: specifically, in February 2015 Gurley warned that late-stage financing was very different than an IPO, and that it had “perverse effects on a company’s operating discipline.” A year later, in April 2016, Gurley said that the “Unicorn financing market just became dangerous…for all involved”, and that included Benchmark:

For the most part, early investors in Unicorns are in the same position as founders and employees. This is because these companies have raised so much capital that the early investor is no longer a substantial portion of the voting rights or the liquidation preference stack. As a result, most of their interests are aligned with the common, and key decisions about return and liquidity are the same as for the founder. This investor will also be wary of the dirty term sheet which has the ability to wrestle away control of the entire company. This investor will also have sufficient angst about the difference between paper return and real return, and the lack of overall liquidity in the market. Or at least they should.I suspect this, more than anything, explains this unprecedented lawsuit.

The Uber Outlier

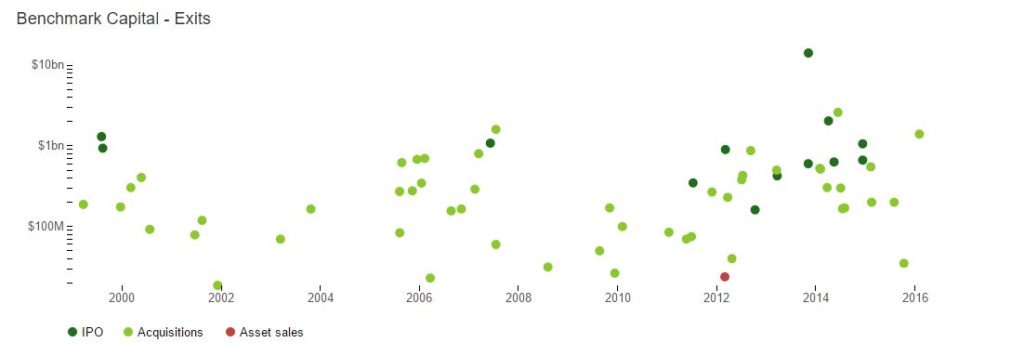

Benchmark is one of those most successful venture firms ever. Founded in 1995 with a commitment to early stage funding, the firm has, going by this chart from CB Insights been an investor in 14 IPOs, 11 in the last five years (the chart shows 13 and 10; I added Snapchat, which IPO’d earlier this year).

The company’s investments include Twitter, Dropbox, Instagram, Zendesk, Hortonworks, New Relic, WeWork, Grubhub, OpenTable, and many more; according to CB Insight, since 2007, the companies Benchmark has invested in have exited (via IPO or acquisition) for a combined $75.96 billion

That, though, simply highlights what an outlier Uber is, at least on paper. Uber’s most recent valuation of $68.5 billion nearly matches the worth of every successful Benchmark-funded startup since 2007. Sure, it might make sense to treat company X and founder Y with deference; after all, there are other fish in the pond. Uber, though, is not another fish: it is the catch of a lifetime.

That almost assuredly changed Benchmark’s internal calculus when it came to filing this lawsuit. Does it give the firm a bad reputation, potentially keeping it out of the next Facebook? Unquestionably. The sheer size of Uber though, and the potential return it represents, means that Benchmark is no longer playing an iterated game. The point now is not to get access to the next Facebook: it is to ensure the firm captures its share of the current one.

This, I would note, is a lesson founders should learn: Kalanick was resolutely opposed to an IPO, claiming he would wait “as long as humanly possible”; his delay, though, completely flipped the incentives of Kalanick and his early investors. While in most companies the venture capitalists have to worry about their reputation along with their capital, in the case of Uber there is simply too much money at stake: transforming a $68 billion paper return to a real return (and guaranteeing a per partner return in the nine figures) is worth whatever reputational damage is incurred along the way.

In other words, an iterated game is good for founders: it ensures venture capitalists are nice. Single move games, though, which Uber has become, often end badly for everyone, particularly founders.

Diminished Uber

Understanding that Benchmark is focused on achieving liquidity on its all-time greatest investment suggests two potential outcomes:

There is a third possibility: that Uber broadly and Kalanick specifically are in big trouble when it comes to Waymo’s lawsuit against the company, and that Benchmark is making clear that it is not culpable. A full six pages of Benchmark’s lawsuit were dedicated to describing Kalanick’s role in the Otto acquisition and Benchmark’s obliviousness to alleged wrongdoing; I noted when the lawsuit was filed that it, more than any of Uber’s scandals, had the potential to be Kalanick’s doom, and apparently Benchmark agrees (although, of course, one should question why Gurley, then an Uber board member, apparently declined to do more digging on a $680 million acquisition).

- The most straightforward is that Benchmark hopes to push Uber to an IPO sooner-rather-than-later; clearly Kalanick was an obstacle as CEO, and according to reports, has sought to reestablish control of the company via his control of the board, driving away Meg Whitman, who was reportedly Benchmark’s choice for CEO.

- This also explains the urgency of this suit: Benchmark is trying to prevent Kalanick from naming two more members to the board, further complicating the CEO selection process.

- The other potential outcome is that Benchmark is looking for an exit. Softbank, which is looking to dominate car-sharing globally, has reportedly had discussions with Benchmark and other investors about buying their shares; reports have been mixed as to who wants to make a deal — Kalanick or Benchmark — but if it is the latter a lawsuit is an excellent way of getting the former to agree to a sale.

What is without question, though, is that whatever outcome results from this mess will be a suboptimal one; most Uber critics still fail to appreciate that the ride-sharing market is demand driven, which meant Uber really did have a chance to be the transportation behemoth of much of the world. Now the company is retreating throughout Asia, is on the regulatory run in Europe, and stuck in a fight it should have never drawn out with Lyft in the United States. Perhaps Benchmark will get its all-time great return, reputations be damned. It seems unlikely its return will be what it once might have been.

0 comments:

Post a Comment