Which is why increased investment in knowledge, data and innovation is required to maintain economic growth. JL

Nicholas Bloom and colleagues report in Vox:

Data on the research effort across all industries shows the costs of extracting ideas have increased sharply. We see a continuing stream of innovations. There have been technological improvements, but these require the devotion of ever-growing amounts of resources to maintain rates of improvement. But, just as newer oil sources are increasingly costly to extract, coming up with new ideas is getting more expensive. This suggests that unless research inputs are continuously raised, economic growth will continue to slow in advanced nations.

Growth in the US and Europe has been falling for several decades – from 4% per year in the 1950s and 1960s to 2% in the 2010s. The major driver of slowing growth is the slowing rate of productivity growth (Fernald 2015). And slow growth is a major factor behind political protest movements that contributed to the votes for Brexit and President Trump. Will this slowdown in growth persist, or is a ‘fourth industrial revolution’ about to begin, possibly encouraged by breakthroughs in computing, robotics, and artificial intelligence?

This debate has morphed into an argument about how many innovations are out there to discover. Optimists and pessimists alike think of discovering productivity improvements as similar to drilling for oil. There are quantities beneath the earth’s surface waiting to be pumped out – but there’s a fixed amount, and once it’s gone, it’s gone. Pessimists like Gordon (2016) argue that we’ve extracted almost all the ‘oil’ of productivity growth already. Nothing as life-enhancing as the indoor toilet could possibly still be out there awaiting discovery. Optimists like Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2014) suggest that new technologies signal endless golden geese, ready for plucking.

We argue that a single-minded focus on the quantity of undiscovered ideas is unhelpful. It is not just how many ideas for productivity growth are left, but what it would cost to get them out of the ground – and, crucially, how much we’re prepared to spend to do it. For a long time, geologists have been forecasting ‘peak oil’, only to be surprised by new deep-sea discoveries and shale oil. We, likewise, see a continuing stream of innovations. But, just as newer oil sources are increasingly costly to extract, coming up with new ideas is getting more expensive.

Measuring the cost of ideas

In a new study, we show that the costs of extracting ideas have increased sharply over time (Bloom et al. 2017). In other words, the innovation bang for the R&D buck (or ‘research productivity’) has declined. In an accounting sense, therefore, low productivity growth in the economy is a direct consequence of research effort failing to increase fast enough to offset declining research productivity. If we want to restore economic growth, we need to pay for it.

We measure declining research productivity in a wide variety of industries, products, and firms. To do this, we find places where we could measure both the inputs to research (research expenditure or effort) and the outputs from the same research (productivity improvements) over time. Wherever we look, the amount of research effort needed to achieve a given proportional improvement in productivity has increased – often dramatically so.

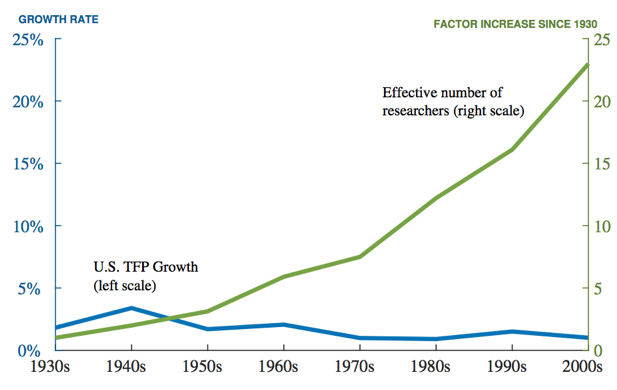

Consider the aggregate level. Figure 1 plots two lines. The first, in blue and corresponding to the left vertical scale, is US total factor productivity growth (the part of output growth left after accounting for inputs of labour, capital and other factors). It declines gently over time. This is our measure of the output of economy-wide research.

The second line, in green and corresponding to the right scale, is the effective number of researchers in the economy. This is our measure of the input of economy-wide research. It increases more than 20-fold. So, more than 20 times as many researchers are needed today to generate about the same amount of productivity growth as 80 years ago.

Figure 1 US total factor productivity growth and number of researchers, 1930s-2000s

Note: The idea output measure is TFP growth, by decade (and for 2000-2014 for the latest observation). For the years since 1950, this measure is the BLS Private Business Sector multifactor productivity growth series, adding back in the contributions from R&D and IPP. For the 1930s and 1940s, we use the measure from Robert Gordon (2016). The idea input measure is gross domestic investment in intellectual property products from the National Income and Product Accounts, deflated by a measure of the nominal wage for high-skilled workers.

If research productivity is declining at the aggregate level, it does not imply that the same must be true for individual products or industries. For this reason, we also examine as many case studies as we could find for which we could carefully measure the inputs and outputs of a given type of research. We find that research productivity has declined in every case.

Moore’s Law is a good example. Our measure of research output here is the famous doubling every two years of the density of computer chips. But the input required to do this – the number of researchers required – is today more than 18 times larger than the number required in the early 1970s. Moore’s Law is not a law of nature, but rather is viewed by the tech industry as a goal to be achieved. Achieving this goal has required massive increases in research investment to maintain the constant doubling time for chip density.

Our research shows that this pattern holds across a range of case studies. Whether we look at crop yields for corn and soybeans, or medical innovations that reduce mortality from heart disease and breast cancer, we find a similar trend. There have been technological improvements, but these require the devotion of ever-growing amounts of resources to the research process to maintain steady rates of improvement. We even find a similar pattern using data at the firm level.

To our mind, this is convincing evidence that ideas are becoming more expensive to find. Unless we keep raising research inputs, economic growth will continue to slow in advanced nations such as the US.

Diminishing returns to research

It is harder to understand why ideas are getting harder to find. At one level, our work suggests that research is like any other input – there are likely to be diminishing returns. These days, pushing the frontier of knowledge out requires mastering an ever-larger body of knowledge, meaning that students have to stay longer in university, and researchers increasingly work in larger teams whose members are more specialised. This all pushes up costs.

Returning to the oil metaphor, we are digging deeper into a trickier part of the rock. Of course, we could be wrong and humanity may have just have been chipping away at a particularly hard point that will soon give way, creating decades of cheap ideas. This is the hope of those who emphasise the revolutionary power of artificial intelligence and the ‘singularity’ – an accumulation of technology that triggers runaway growth at some point in the future. Although we all enjoy science fiction, history books are usually a safer guide to the future. In this case, history suggests that large increases in research effort are needed to offset its declining productivity.

0 comments:

Post a Comment