Marty Swant reports in Adweek:

170 VR-related companies of varying types and sizes are expected to pitch their products on the crowded CES showroom floor, up from 70 last year. The technology immediately impresses the user and offers “unlimited potential,” (but) the question then becomes: What do you do with it? The mass consumer isn’t going to love VR for the sake of VR. “A headset is a paper weight without good content,”

Each January, tech experts at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas peer into their crystal balls and declare that “this is the year of something.”For about 10 years, it was the “year of mobile.” After that it was the “year of connected cars,” which was then eclipsed by “the year of smart devices.” Now, some say 2018 could be the year of virtual reality. In fact, nearly 170 VR-related companies of varying types and sizes are expected to pitch their products on the crowded CES showroom floor, up from 70 last year.At CES, the CEOs of Hulu and Turner will discuss the future of media, focusing in part on VR content.While the annual electronics show is largely focused on hardware, on Wednesday the CEOs of Hulu and Turner will take the CES stage to discuss the future of media, focusing in part on VR content—what might it look like when viewers and stories are unbound from the confines of a two-dimensional screen?“We’re calling this the ‘Race to the Center,’” says Turner CEO John Martin. “Traditional digital and tech players are trying to become much better at creating premium content, while premium content such as ours are trying to become better at creating technology.”This “race” Martin references is also the make-or-break question the VR industry faces as it looks to hit a critical mass. But what needs to happen first is the “chicken-and-egg” question: mass hardware adoption or the creation of compelling content?Will 2018 be the year they crack it?The cost of pricey headsets

For Hulu, the search is on for a golden goose. Early this year, the company will release its first VR series Door No. 1, a choose-your-own-adventure program with sponsors Bumble and Nissan woven into the storyline. However, industry insiders admit VR has yet to have a blockbuster moment, and what exactly that will look like is a question that keeps execs up at night. In other words, VR hasn’t hit upon the kind of cataclysmic, traffic-driving event similar to how Snapchat drove the adoption of vertical video or Niantic’s mobile game Pokemon Go drove understanding of augmented reality.“A headset is a paper weight without good content,” says Loren Hammonds, a programmer for the film and experiential selections at the Tribeca Film Festival, which has showcased VR material since 2012.Oculus RiftAlthough growing, the headset market is still relatively small. According to market research firm International Data Corp., headset sales are expected to increase from 9.6 million last year to 59.2 million in 2021. (The only company to release official numbers is Sony, which in December said it sold 2 million in 2017, doubling the 1 million mark it announced in June, but it’s less than impressive compared to the 344.3 million smartphones sold worldwide in the first quarter of 2017.)Then there’s the cost, which remains a factor for a majority of would-be VR buyers. According to an IDC study, lack of content coupled with high costs stands as the main hurdle for 64 percent of potential headset buyers surveyed. For example, the price tag on an Oculus Rift is $400 while the HTC Vive sells for $600. Both require a powerful PC, adding another $600 and $2,000 for the privilege. However, the price barrier is beginning to drop. Last year, Facebook announced plans for the $200 Oculus Go (scheduled to hit the market early this year), with technology that allows for more freedom and interactivity than basic $100 models such as the Samsung Gear VR or Google View. Lenovo, which began selling a $200 mobile VR headset last year, is also working on a stand-alone headset of its own that runs on Google’s Daydream VR platform and is expected to debut this week at CES.For their part, media companies, brands and ad agencies say they’d be willing to create more content if the audience were larger.“When I think about VR, I think ‘is this the next smartphone?’” says Tom Goodwin, Zenith’s head of innovation. “There are going to be 2 billion or 3 billion [smartphones] on the planet. Is this the next games console? In this case, is it going to be covering 200 million [units]? Or is this the next Segway where it’s going to be 200,000? I think it’s probably kind of like the next console. It probably is going to be a significant platform.”Media play the long game

Such thinking has spurred media companies that were slow to move on new technologies in the past to plunge ahead. Chaki Ng, an executive at Viacom’s R&D lab, Viacom Next, says while his company waited five years to build its first app, it’s now churning out new VR concepts every few months rather than the typical one- or two-year timeline. Ng says even his venture capitalist friends investing in VR are prodding him, saying, “‘Chaki, you need to create more content.’”That’s also true for Viacom-owned Nickelodeon, which is also amping up its own VR R&D. Chris Young, svp of Nick’s Entertainment Lab, says today’s VR market looks similar to the early days of the internet when there was a small group of people developing pages for a small audience.“If you told people you were launching cartoons on cellphones, they would literally laugh you out of the conference room,” he says. “But that’s not the case today.”"Dear Angelica," a VR movie from Oculus Story StudioDear AngelicaExperts are still debating whether hardware or content will be the trigger point for VR. Lewis Ward, IDC’s research director for gaming and VR, is in the content camp. “It is really critical for companies that have deep pockets and that are planning a long-term investment to plan services to show what’s possible, and then other people will follow,” he says. After all, who would buy a video game console without any games to play, or who would sign up for Netflix if there weren’t anything to watch?Jason Rubin, vp of content for Oculus, says the goal is to evolve VR as much in five years as it took mobile to do in 10 or the PC era to do in 40. While the technology immediately impresses the user and offers “unlimited potential,” he says the question then becomes: What do you do with it?

“The devices to input virtual reality into you will get better,” he says. “Eventually it will expand past your eyes, which is what we’re focused on now, and your hands with haptics. We’ll do better with your ears and 3-D sound will sound better. We’ll start impacting your skin and you’ll feel things and we’ll be able to simulate wind. And one day we’ll actually get your inner ear and you’ll physically feel like you’re moving, which is something you can’t do today.”

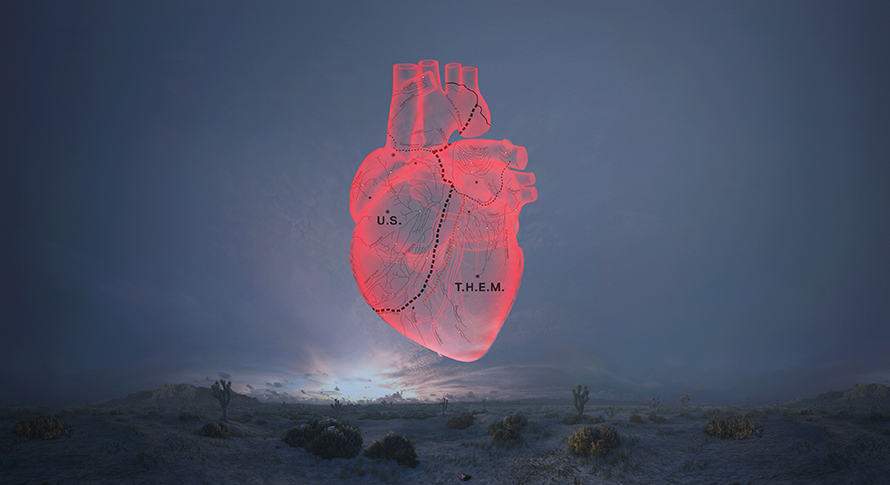

While VR’s time to mass market appeal remains an open question, one way to help jump-start it would be for a cash-rich company like Facebook or Google to take an Amazon-style approach, subsidizing hardware prices or giving it away, generating revenue from content and ads. (Monetizing VR remains an issue.)After three years in the hype cycle, the VR industry is now under pressure to show results. Brian Blau, an analyst at Gartner, says VR needs “four legs” to stand on its own: accessible hardware, affordable hardware, quality content, and also an ecosystem like Apple and Microsoft, where hardware and software coexist.It’s not the case that quality content isn’t already on the market. While many of the TV networks are just getting started, some of the earliest VR standouts have already been released by indie producers and small production companies. Alejandro González Iñárritu’s “Carne y Arena,” a VR experience about immigrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border, earned him a special Oscar in 2017. Gabo Arora’s emotional VR Experience, “The Last Goodbye,” shown at last year’s Tribeca Film Festival, allowed viewers to visit a concentration camp alongside a Holocaust survivor. At this month’s Sundance, former Pixar animator Jessica Shamash will premiere her VR experience for “Wolves in the Walls,” where the viewer gets to become an imaginary character inside of a fairy tale based on the Neil Gaiman children’s book."Carne y Arena" is a VR experience about immigrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border.LACMABut even production companies creating some of the best VR films say better hardware and better content go hand in hand. As the headset improves, so too will the experience, says Madelaine Guppy, chief commercial officer at the VR studio Here Be Dragons, which has produced VR projects for Nike, GE and SNL, along with an Emmy-nominated VR film for Mr. Robot.“I don’t think any other medium we’ve done that with before, where we’re putting collective content into a technical bracket rather than an institutional bracket,” she says. “And I think that is kind of becoming quite dangerous, especially when VR is its own kind of genre. You’d never just judge everyone on TV as TV… But with VR that’s what’s happening.”The challenge of marketing VR content

Then there’s the question of marketing. How do you market something that’s impossible to fully understand until it’s been experienced? While there are dozens of high-quality, stand-alone VR films and interactive experiences, many consumers simply don’t know about them. (And producers are still working out some of the kinks—for one, shaky 360-degree videos have infamously made viewers nauseous.)PlayStation’s campaign, “Feel Them All," shows what it's like to play VR games.To that end, Sony, Samsung and Facebook all ran ad campaigns in 2017 aimed at raising VR’s profile while explaining its frisson: the immersion factor. But even that effort was limited given the promotion’s two-dimensional format. Last fall, hoping to change that, Facebook hired a new agency to market Oculus. It debuted with a campaign for Rift inviting users to “step into Rift.” Meanwhile, PlayStation’s campaign, “Feel Them All,” attempted to show what it’s like to play VR games such as Gran Turismo Sport, Resident Evil 7: Biohazard, and The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim VR.“It’s really challenging to explain virtual reality and what the expectation is when you put on the headset,” says Mary Yee, PlayStation’s vp of marketing. “We’ve always been talking about transporting you to new worlds, and this new campaign is really talking about what it feels like when you get there.”A new reality

In March, the genre will receive a big boost with the release of director Steven Spielberg’s film adaptation of Ready Player One, a novel set in a future where everyone spends their days and nights in VR. While at CES, HTC Vive and Warner Bros. are expected to announce the next steps in their joint partnership to promote VR and the movie itself, bolstering several 2-D trailers released late last year.In the end, says Ryan Hoopingarner, executive director of marketing for HTC Vive, “The mass consumer isn’t going to love VR for the sake of VR. They’re going to love it because the things that they already love can be found there.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment