But the cost for bigger companies will probably add up to the tens of millions and may take years. So cognizance of the potential financial and operational benefits had better be certain. JL

Robert Klara reports in Ad Week:

The past couple of years have seen a multitude of companies, including many household names, changing what they’re called. (Recently) corporate name changes have had more to do with not getting pigeonholed into a single category—that’s why Jamba scuttled the Juice—or opting for shorter names because they’re much easier to recognize on handheld screens. There are hundreds of consumer touch points to be updated: packaging, uniforms, point-of-sale merchandising, wall art, printed collateral and the digital elements, from the website to the app to digital ads. The process of changing Federal Express to FedEx took three years. The change accompanied a streamlining of company operations, which altogether cost $100 million.

Bob Purcell is a successful consultant, a Massachusetts transplant who’s quite happy to enjoy the year-round warmth of Southern California. But Purcell still vividly recalls his corporate days on the East Coast when, between 1986 and 1994, he was the chief marketer for Dunkin’ Donuts. And if you ask Purcell about his Dunkin’ Donuts days, he’ll tell you about a huge decision he almost made but ultimately didn’t: changing the brand’s name.

Hold on—didn’t Dunkin’ just do that, you ask? It did. Eleven months ago, the 68-year-old chain announced that Dunkin’ Donuts would be dropping the “Donuts” and becoming just Dunkin’. But Purcell had considered a virtually identical move 25 years ago. His in-house ad agency had suggested renaming the place Dunkin’s, a simple possessive that would allow for the easy promotion of various menu categories—Dunkin’s Sandwiches, Dunkin’s Coffee, and so on.

But that never happened. It wasn’t because there was anything wrong with a one-word name or because fellow executives didn’t like it. It never went down for one very specific reason.

“The operational issues—that’s what held us back,” Purcell said. “We just didn’t need those headaches.”

What sort of headaches? Well, the price tag, for one. A corporate name change is an expensive undertaking. But that was hardly his only concern. Purcell had just introduced a number of line extensions to the menu, including dark roast and Coolattas, and he was worried that a name change would be distracting. He had also worked very hard to repair the chain’s damaged relationship with franchisees. They had filed suit against corporate, and Purcell had helped settle it. With the hard feelings only recently mended, Purcell said, “the last thing you needed was to ask franchisees to change a sign. We couldn’t just go back at that point and ask them to shoulder [the costs.]” Ultimately, for these and other reasons, “we just put it on the back burner.”

Purcell’s experiences might be a quarter century old, but the hurdles associated with changing a company’s name—the ones he feared and plenty of others—are as relevant as ever. What’s more, they are items on the desks of many executives right now. The past couple of years have seen a multitude of companies, including many household names, take the ambitious step of changing what they’re called.

Why would a brand change its name?

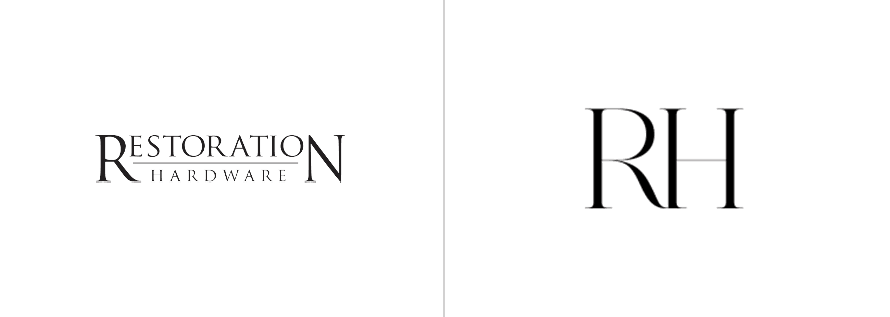

In 2019, for example, Jamba Juice nixed the “Juice,” and Vacation Rentals by Owners became Vrbo. Last year, Weight Watchers became WW and Dunkin’ Donuts finally got to be just Dunkin’. Restoration Hardware abridged its name to RH in 2017, and Hewlett-Packard began going by HP in 2015.

In fact, name changing—most frequently, it amounts to name shortening—is a tactic pioneered by some of the world’s biggest brands, including Apple (which dropped the “Computer” from its name in 2007), Starbucks (which lost the “Coffee” in 2011) and FedEx, which was known as Federal Express until 2000.

The reasons why companies change their names are as numerous and varied as the companies themselves. Kentucky Fried Chicken became KFC in 1991 to avoid paying a licensing fee that the state of Kentucky had imposed on brands that wanted to use its name. Budget airline ValuJet became AirTran to distance itself from a 1997 crash that killed 110 people. During the internet boom of the late 1990s, some companies found that adding a dot-com to their names worked wonders for their stock prices (at least temporarily).

In more recent years, corporate name changes have had more to do with not getting pigeonholed into a single category—that’s why Jamba scuttled the Juice—or opting for shorter names because they’re much easier to recognize on handheld screens.

The reasons vary. What seldom does is the daunting operational complexity of the job itself.

The process begins

As chief brand officer of Weight Watchers, Gail Tifford led the team that made sure the company’s new name appeared everywhere it had to. And she’s glad it’s over. “It was probably one of the bravest, most audacious projects I’ve ever worked on in my life,” Tifford said.

Weight Watchers became WW to distance itself from the 56-year-old brand’s longstanding associations with weight and dieting in order to focus more on wellness. (The company also coined a new w-heavy tagline, “Wellness that works,” just to hammer that point home.) WW’s name change was especially intimidating, Tifford said, because the company’s operations are so varied and diverse.

WW not only offers 30,000 workshops a week around the world, it publishes magazines, sells cookbooks and offers a range of packaged foods. And these materials are separate from the paperwork—subscription agreements, brochures, and so on—that also had to be changed over. In all, Tifford estimated, there were 1,800 different points of interaction between brand and consumer that needed to go from Weight Watchers to WW.

Geoff Henry, president of Jamba, has a similar experience. Changing a company name, Henry said, “is a massive undertaking that involves all aspects of the organization. Within Jamba, there are hundreds of consumer touch points and elements that need to be updated.” Henry listed just a few of these: packaging, uniforms, point-of-sale merchandising, wall art, printed collateral and, of course, all of the digital elements, from the website to the app to digital ads.

Because of the scale of the assets that need to be switched over, most brands find it best to roll the new name out gradually, a “staged approach,” Tifford called it. “We had a timeline—a brand rollout timeline like you’ve never seen,” she said.

Vrbo is a service that connects travelers with homeowners interested in short-stay rentals of their properties. Founded in 1995, a good 13 years before Airbnb, the company changed its name in March in part because customers had already been pronouncing the VRBO acronym “Ver-boh” anyway. And faced with the mechanics of changing the name, Vrbo decided to prioritize the process by “changing the most visible instances that impact our customers the most first, such as the website, mobile app, social media accounts, and televised and digital ad campaigns,” said chief strategy officer Judy Kay.

Do ecommerce brands have it easier?

Since Vrbo is a web platform, it’s in for a slightly easier time when it comes to implementating of its name change. Altering a name online is always going to be faster and easier (and cheaper) than changing physical infrastructure. Alexandra Watkins, who runs brand-naming consultancy Eat My Words, adds changing a company’s name is, at least, simpler today than it was in the analog era.

“Back in the day, it was hard,” she said. “You’d have to change so many things, even if you were a small company.” But old websites redirect to new ones, she said, and emails can swiftly advise customers of a name change. And as far as all that office paperwork? “Most people don’t even have letterhead [anymore],” she said.

Which of course is true, but brands with a significant physical infrastructure still find themselves with scores of items on the punch list. There’s probably no better example than FedEx, which currently counts 690 planes and nearly 85,000 trucks in its fleet. (The numbers 20 years ago were smaller, but the scale still speaks for itself.) All of those vehicles had to be repainted, a task complicated by the fact that they all had to stay in motion to generate revenue.

“As our operations are always moving, especially across our fleet and aircraft, it’s difficult to find a quiet moment to pull our planes and delivery vehicles out of the field,” said Patrick Fitzgerald, FedEx’s svp of integrated marketing and communications. “It was a far less complicated process to update nondurable assets such as customer packaging and forms.”

Nevertheless, the entire process of changing Federal Express to FedEx took nearly three years. The name change accompanied a broader streamlining of company operations, which altogether cost a reported $100 million.

Burning off the old inventory

When the brand is a restaurant, where margins are low and volume is everything, the nondurables—cups, napkins, bags and other name-bearing items necessary to run a store—are still a valuable part of the investment. So when it came time to order these goods printed with the new name, “we didn’t throw away existing inventory,” Jamba’s Henry said. “It has been planned as a natural transition versus a hard-stop conversion. We’ve worked down our inventory position of the old graphics so that we could deplete the inventory.”

WW did much the same thing, using up the existing stock of products and collateral to avoid having to toss it out. A notable exception was the stockpile of Weight Watchers shirts. Tifford did not think it was worth waiting for all of those to get bought up. “We donated the old T-shirts to homeless shelters,” she said.

For brands with a brick-and-mortar presence, few items are as difficult to switch out as the sign out front. Large, heavy and usually electric, signs aren’t just complicated pieces of infrastructure, they embody just how expensive a systemwide name change can be. For example, according to Signs by Crannie, a full-service sign company which has done work for H&R Block, McDonald’s and Applebee’s, a 10-by-7-foot freestanding sign with internal LED lighting can run upwards of $28,000. Take a system with 500 stores, and it’s easy to see what kind of investment signage alone represents, to say nothing of the site surveying, installation and building-code compliance that accompanies the purchase.

Store signs, Tifford said, have “been the longest process for us.” WW has 800 locations in the U.S. alone, and each one of them will require a new sign. What’s more, the company had to come up with several versions of the new sign, depending on the location. Some signs need to light up. A sign that pops on a dark-brick facade won’t work on one with light-colored bricks, and so on.

“The signs really are a tricky thing,” said Dunkin’s current CMO Tony Weisman, whose team took pains to make sure that while the new signs looked fresh, they wouldn’t look that dramatically different than the existing ones so as not to make the older models look dated and risk putting those units at a disadvantage.

Given the expense of new signage, Dunkin’ also put its franchisees on a generous renovation timeline of five to 10 years. “We’ll ask you to change the sign at the end of that,” Weisman said. That means the changeover to Dunkin’s new identity won’t be immediate. “It’s going to take a few years,” Weisman said.

Weisman isn’t the only chain-store executive whose name-change planning had to be done with franchisees in mind. The restaurant business has a long history of franchisees resentful of being handed the bill for the upgrades headquarters decides on. To forestall potential problems, Jamba’s Henry was careful to include franchisees early in the process.

“The rebranding effort was a massive body of work that involved input from a number of franchisees along the way,” he said, adding that Jamba corporate elected to “co-invest” to help pay the associated costs.

What’s the price tag?

And the process, not surprisingly, is not cheap. Nor is it anything executives feel like discussing. While none of the companies interviewed for this story would get into the final bill associated with a name change—“Even if I did [know],” said WW’s Tifford, “I don’t know if they’d let me share it”—a 2017 Thompson Reuters report on the complexities of adopting a new corporate name advised, “It is an expensive undertaking. … If a company is changing its legal entity name, it can be costly to update the ownership information for all of its IP and other assets. Small companies can expect to spend tens of thousands of dollars on a corporate identity change while global companies can easily spend millions of dollars.”

Some of that money will be spent not on materials, but in labor. At WW, it became at least one employee’s full-time job to oversee the name change. “There was one woman on my team—god bless her—she was the steward,” Tifford said. “She coordinated the work stream across every single function—legal, production, supply chain, consumer product, marketing. We had weekly meetings where they would literally go through and identify every single item that had to be updated.”

Twenty-five years down the line, Purcell, Dunkin’s former marketing chief, is glad the chain finally got around to implementing the shortened name he’d spent so much thinking about back in the day. But he said that for all the troubles associated with changing it, customers had already pretty much changed it in their own minds years before. “Customers were already there,” he said. With their demonstrated love for informal speech, Americans had never really bothered to say they were stopping off at Dunkin’ Donuts.

“[It’s] I’m going to Dunkin’,” Purcell said.

0 comments:

Post a Comment