For all the blather we have had to endure for two decades now about embracing change and innovation and the gales of creative destruction and disruption, the reality is that - as a species - we don't like it very much.

And the bigger the change, the less comfortable we are with what it might portend.

So despite having to pay $20 billion in fines for various infractions and as much as another $9 billion in legal fees, JP MorganChase gave CEO Jamie Dimon a big raise this year. Because neither the bank's directors, nor its shareholders nor its regulators in the US government really wants to contemplate what life might be like with someone different at the helm.

Now the reality is that life under a new leader will probably not be apocalyptic or even noticeably different. The recent CEO change at Citi suggests that large bureaucratic institutions wend their way forward out of habit, momentum and the collective effort of employees fearing a worse fate than being employed there - that being unemployment or work at a less-well-capitalized enterprise. Suffice it to say that many, even in the financial community, will have to pause for a second to remember the name of the guy who left Citi a year or so ago - and may well have to think for a minute before naming the one who replaced him.

By comparison, JP Morgan is in much better shape than was Citi. As the following article explains, its performance relative to various indices is respectable. And that is the performance for which investors and directors pay - at least until the reputational stuff begins to interfere or seriously threaten to reduce financial results. There is, too, a concern that admitting weakness by removing a leader, may threaten their hold on margins, market share and other assets convertible into income.

There is considerable frustration evinced in many quarters at the fact Dimon - or anyone else in power - has not been held accountable for all his bank's alleged or acknowledged misdeeds. But the nature of US law is such that it is far easier to go after an institution than it is to nail an individual with responsibility for ostensibly illegal activity.

So the ironic threat to Mr. Dimon, and to leaders like him, in the long term, is that by keeping easily identifiable people in place rather than attempting to remove them, they become gifts that keep on giving to the public entities that oversee them. It is that trade-off between the financial impact of past and current behavior versus the potential uncertainty of change may well be what keeps change at bay. JL

Dan McCrum comments in the Financial Times:

If you are angrily asking why has Jamie Dimon got a pay rise, you should really be asking why the hell he is still in charge of the bank.

So the bank has paid around $20bn in fines, penalties, etc, but Wall Street’s favourite chief executive is going to get a raise.

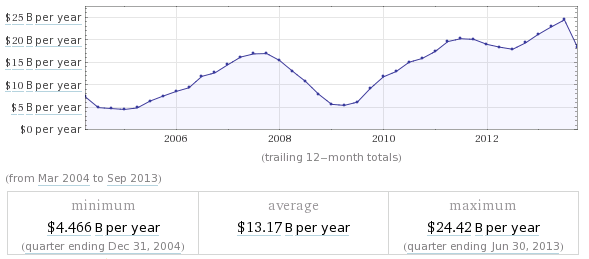

Without being an apologist for the bank, we think this is the reason he might feel justified in asking for some more green (with help from Wolfram Alpha):

Profitable through the crisis, and much more profitable afterwards than before. If you’re prepared to forgive the whole Whale episode and look at the earnings, he seems to have done something right.

Of course, a massive bank with a presence in so many parts of the US economy is going to do well as housing, growth, employment, corporate profits and the rest recover.

We could almost play spot-the-difference with the Wells Fargo version of that chart. A smoother progression but a similar trajectory.

Still, things are on the up and up.

Of course, fines and penalties are about more than just monetary matters. JP Morgan is big enough to shrug off $20bn, but you might well ask who was in charge of this operation and how does he still have a job?

The thing is, either he is held accountable or he isn’t. Docking his pocket money is rather beside the point.

But if investors and the board aren’t, perhaps it’s because they are taking their lead from the government, which has not seen fit to go after individual executives.

This is not to say that Jamie Dimon should have been prosecuted, far from it. It is rather to say that the Whale, the fines, the crisis have all been forgiven already. Dimon’s pay rise is just the most recent sign that it is back to business as usual.

Jed Rakoff, a Federal Judge in New York’s Southern District who has overseen a lot of the post crisis settlements, has written one of the best analyses of why there were no prosecutions:

My point is that the Department of Justice has never taken the position that all the top executives involved in the events leading up to the financial crisis were innocent; rather it has offered one or another excuse for not criminally prosecuting them—excuses that, on inspection, appear unconvincing. So, you might ask, what’s really going on here? I don’t claim to have any inside information about the real reasons why no such prosecutions have been brought, but I take the liberty of offering some speculations.Those speculations are that prosecutors had other priorities, the government in parts of the mortgage market at least was encouraging the fun, and the third:

The final factor I would mention is both the most subtle and the most systemic of the three, and arguably the most important. It is the shift that has occurred, over the past thirty years or more, from focusing on prosecuting high-level individuals to focusing on prosecuting companies and other institutions.As Rakoff argues, it is much, much easier to force a company to cough up than do the hard work of proving an individual guilty, a weakness in the prosecutorial system that needs addressing. It isn’t corporate governance per se, but if the Dimon haters are after something they can affect, the cause is there ready and waiting.

0 comments:

Post a Comment