The need for enhanced cyber-security protocols is hardly new news to business. Until recently, however, most had relied primarily on a 'Maginot Line' response: bigger, stronger walls around their data. As students of history will recall, the French Maginot Line failed to stop determined Nazi military assault in the early days of WWII. Similarly, the attitude among hackers is that walls were made to be breached.

Hackers rely on the knowledge that resourced-constrained and cost-conscious companies are always attempting to evaluate the trade-offs between investments in security and the potential benefits. In corporate budgeting terms it is especially hard to justify the ROI on the possible circumvention of a potential problem. There is no gain, per se, just the ostensible prevention of a theoretical loss. Not something for which itchy investors are likely to praise management.

So, businesses have begun to take the offensive in hopes of frustrating hackers rather than waiting for the next incursion. As the following article points out, there are some risks to this, including the fact that planting certain types of false data may actually be illegal. However, it is hard to imagine law enforcement officials actually going after a company that does so in its own defense, especially given the the problem's growth rate, the failure of static responses - and the fact that some of the US and Europe's most dangerous strategic competitors - China and the Middle East - may be behind some of the attacks. JL

Ellen Nakashima reports in the Washington Post:

In the parlance of network security, digital deception is known as a type of “active defense,” a controversial and sometimes ill-defined approach that could include techniques as aggressive as knocking a server offline. U.S. officials and many security experts caution companies against taking certain steps, such as reaching into a person’s computer to delete stolen data or shutting down third-party servers. Brown Printing Co., which prints popular magazines and catalogues, knew that it had valuable assets in its computer systems and that those assets — online editions and subscriber databases — were increasingly at risk with the proliferation of cyber-espionage.

And so, to confront one of the newest and most damaging crimes, it turned to one of the oldest tricks in human history: deception.

The Waseca, Minn., company began planting fake data in Web servers to lure hackers into “rabbit holes” in the hopes of frustrating them into giving up. The bait was varied — including bogus user log-ins and passwords and phony system configuration files. Anyone who took it was being watched by Brown, their computer locations tagged and their tactics recorded.

“We’re taking the hackers’ strengths and we’re making it their weaknesses,” said Nathan Hosper, a senior information technology officer at Brown. “They get caught up in this cycle of fake information.”

Brown is only one of a number of companies that are adopting tactics long used by law enforcement and intelligence agencies to turn the tables on hackers.

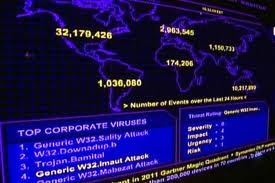

The emerging trend reflects a growing sense in industry that companies need to be more aggressive in fighting off intruders as the costs of digital espionage soar. The theft of intellectual property and other sensitive documents — from military weapon designs to files on contract negotiations — is so rampant that senior U.S. officials say it may be the most significant cyberthreat the nation faces over the long term.

“Companies are tired of playing defense,” said Michael DuBose, a former chief of the Justice Department’s Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section who now handles cyber-investigations for Kroll Advisory Solutions. “They want to feel like they actually can fight back. Most of us in the industry agree that we ought to push the envelope to protect the rights and properties of U.S. businesses.”

Those actions probably would violate federal law, FBI officials said. The bureau also warns that the use of deceptive tactics could backfire — hackers who identify data as bogus may be all the more determined to target the company trying to con them.

Just how far companies should be allowed to go to defend themselves is the subject of intense debate in the industry and on Capitol Hill.

Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Mich.), the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, said at a recent conference that disrupting another party’s server is an offensive act that could trigger retaliation that a company might not be prepared for. “It’s best not to go punch your neighbor in the face before you hit the weight room,” he said.

Nonetheless, most experts say deceptive tactics fall within legal boundaries, as long as fake data are planted only inside a company’s network and do not damage a third party’s computer system. Such tactics, they argue, can also be highly effective.

Digital deception tools date back at least 20 years in the academic research community. They are sometimes called “honey pots,” reflecting the notion that they not only attract hackers but keep them inside a network long enough so that they can be watched.

“The use of deception is a very powerful tool going back to Adam and Eve,” said Salvatore Stolfo, a Columbia University computer science professor who has created a technique that uses decoy data to trick intruders. “If the hackers have to expend a lot of energy and effort figuring out what’s real and what’s not, they’ll go elsewhere.”

Anecdotal evidence suggests the techniques can work in the private sector.

Stolfo, whose research is funded by the Pentagon and the Department of Homeland Security, tested his technology with a major U.S. bank two years ago. The bank put $1,000 in an online decoy account registered to a fictitious user, then Stolfo exposed the account to malware from Web sites controlled by hackers. Within three days, the bank began seeing attempts to shift money from the dummy account into a real account, whose owner the bank knew, Stolfo said.

The bank shut the fake account. Had it been a real theft, the bank would have turned the culprit in to the FBI, said Stolfo, who has created the firm Allure Security to bring the technology to market.

In another case, a Northern Virginia cybersecurity firm that works closely with U.S. intelligence agencies and has been targeted by hackers in China has used honey pots to collect data on intruders. The firm, whose director requested anonymity to avoid drawing attention to the company, has created encrypted data files labeled with the names of Chinese military systems and put them in folders ostensibly marked for sharing with the National Security Agency and the CIA.

With such bait, the firm has been able to document how individual hackers work and has linked their pseudonyms, which are sometimes embedded in source code, to real people. The honey pot “has given us a lot of information about these guys,” the director said. “It confounds them.”

Some experts point out that deceptive tactics can inadvertently ensnare ordinary customers and possibly pose liability risks. But software companies say they are mindful of that danger.

Mykonos Software, a San Francisco company that created the tools used by Brown Printing, began using fake data commercially about three years ago, said David Koretz, the firm’s founder and general manager. Mykonos places the false data on clients’ Web sites in places no ordinary customer would look, such as in source code and in configuration files that only a real system administrator or a hacker would find useful.

“When the good guy uses the site, they’re never going to touch the fake things,” Koretz said. When a hacker hits a piece of false code, Mykonos, which is owned by juniper Networks, tags him with a “super cookie,” a digital file that tracks his device. “We’re now tracking every bad thing he does,” he said.

Sometimes, he said, a hacker trying to trick a client’s server into giving him access might be met with a surprise. He might see a Google Map pop up on his screen identifying his location, next to a list of nearby lawyers and a note reading, “It looks like you’re going to need a criminal attorney.”

Within the first week that Brown Printing installed the deception tools in 2010, it detected 375 suspicious probes against its Web sites. “That was the first time that we could say, ‘Wow, we’re seeing those events and we know what’s occurring,’ ” said Hosper, the senior information technology officer.

The bottom line, he said, is the feeling that “you’re no longer just having to sit passively by and take it. You have the ability to take control of the situation.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment