The farmers are fighting back by hacking the systems - and using bootleg software from places like the Ukraine to do it. This is part of the much larger battle about what pricing and ownership mean in the age of technology. The winner is not yet clear. JL

Cory Doctorow reports in BoingBoing and Jason Koebler reports in Motherboard:

John Deere is fighting farmers who say they want to fix their own tractors and access their data by saying that doing so violates the prohibition on bypassing copyright locks. Deere's joined by auto manufacturers and many other corporations, all arguing that since the gadgets you buy have software, and since that software is licensed, not sold, you are a licensee, and you have to use the gadget according to the license terms, which spell out where you buy your service, parts, consumables, apps.

Motherboard To avoid the draconian locks that John Deere puts on the tractors they buy, farmers throughout America's heartland have started hacking their equipment with firmware that's cracked in Eastern Europe and traded on invite-only, paid online forums.

Tractor hacking is growing increasingly popular because John Deere and other manufacturers have made it impossible to perform "unauthorized" repair on farm equipment, which farmers see as an attack on their sovereignty and quite possibly an existential threat to their livelihood if their tractor breaks at an inopportune time.

"When crunch time comes and we break down, chances are we don't have time to wait for a dealership employee to show up and fix it," Danny Kluthe, a hog farmer in Nebraska, told his state legislature earlier this month. "Most all the new equipment [requires] a download [to fix]."

The nightmare scenario, and a fear I heard expressed over and over again in talking with farmers, is that John Deere could remotely shut down a tractor and there wouldn't be anything a farmer could do about it.

"What you've got is technicians running around here with cracked Ukrainian John Deere software that they bought off the black market"A license agreement John Deere required farmers to sign in October forbids nearly all repair and modification to farming equipment, and prevents farmers from suing for "crop loss, lost profits, loss of goodwill, loss of use of equipment … arising from the performance or non-performance of any aspect of the software." The agreement applies to anyone who turns the key or otherwise uses a John Deere tractor with embedded software. It means that only John Deere dealerships and "authorized" repair shops can work on newer tractors.

"If a farmer bought the tractor, he should be able to do whatever he wants with it," Kevin Kenney, a farmer and right-to-repair advocate in Nebraska, told me. "You want to replace a transmission and you take it to an independent mechanic—he can put in the new transmission but the tractor can't drive out of the shop. Deere charges $230, plus $130 an hour for a technician to drive out and plug a connector into their USB port to authorize the part."

"What you've got is technicians running around here with cracked Ukrainian John Deere software that they bought off the black market," he added.

Kenney and Kluthe have been pushing for right-to-repair legislation in Nebraska that would invalidate John Deere's license agreement (seven other states are considering similar bills). In the meantime, farmers have started hacking their machines because even simple repairs are made impossible by the embedded software within the tractor. John Deere is one of the staunchest opponents of this legislation.Image: Cartec-Systems

"There's software out there a guy can get his hands on if he looks for it," one farmer and repair mechanic in Nebraska who uses cracked John Deere software told me. "I'm not a big business or anything, but let's say you've got a guy here who has a tractor and something goes wrong with it—the nearest dealership is 40 miles away, but you've got me or a diesel shop a mile away. The only way we can fix things is illegally, which is what's holding back free enterprise more than anything and hampers a farmer's ability to get stuff done, too."

I went searching for one of the forums where pirated John Deere firmware is sold. After I found it, I couldn't do much of anything without joining. I was sent an email with instructions, which required me to buy a $25 dummy diagnostic part from a third-party website. Instead of the part, I was sent a code to join the forum.

Once I was on it, I found dozens of threads from farmers desperate to fix and modify their own tractors. According to people on the forums and the farmers who use it, much of the software is cracked in Eastern European countries such as Poland and Ukraine and then sold back to farmers in the United States.

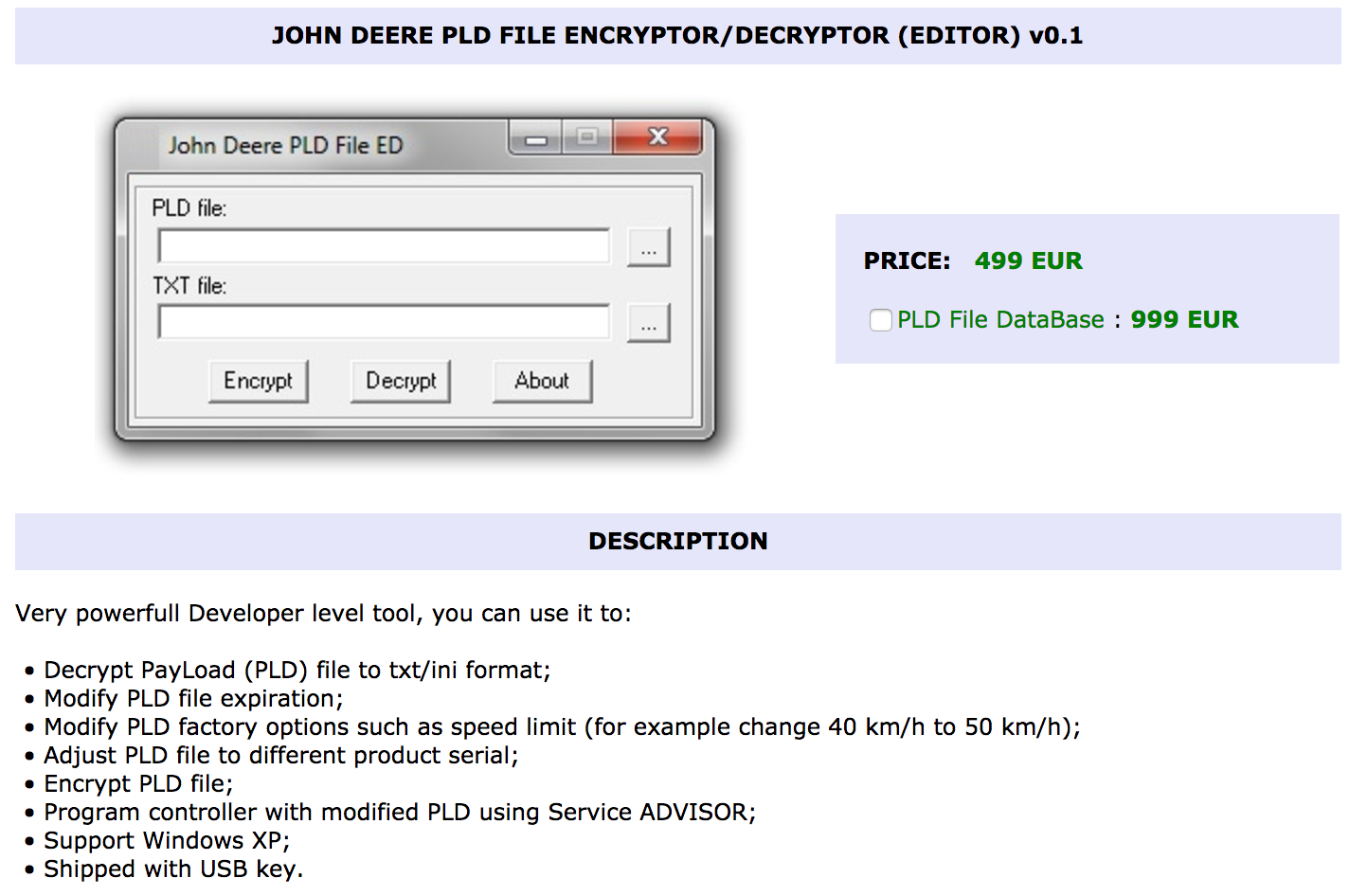

Among the programs I saw being traded:

John Deere Service Advisor: A diagnostic program used by John Deere technicians that recalibrate tractors and can diagnose broken parts. "It can program payloads into different controllers. It can calibrate injectors, turbo, engine hours and all kinds of fun stuff," someone familiar with the software told me.

John Deere Payload files: These are files that specifically program certain parts of the vehicle. There are files that can customize and fine-tune the performance of the chassis, engine, and cab, for instance.

John Deere Electronic Data Link drivers: This is software that allows a computer to talk to the tractor. "The EDL is the required interface which allows the Service Advisor laptop to actually communicate with the tractor controllers," the source told me.

A reverse engineer who goes by Decryptor Tuning, who I met on a forum, told me they distribute programs that are "usually OEM software that is freely available but must be licensed."

"If things could get better, [companies like John Deere] should be forced to freely distribute the same software dealers have," they said. "And stop locking down [Engine Control Module] reading functionality. They do this to force you to use their services, which they have a 100 percent monopoly on."

Also for sale (or free download) on the forums are license key generators, speed-limit modifiers, and reverse-engineered cables that allow you to connect a tractor to a computer. These programs are also for sale on several sketchy-looking websites that are hosted in Europe, and on YouTube there are demos of the software in operation.

On its face, pirating such software would seem to be illegal. But in 2015, the Librarian of Congress approved an exemption to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act for land vehicles, which includes tractors. The exemption allows modification of "computer programs that are contained in and control the functioning of a motorized land vehicle such as a personal automobile, commercial motor vehicle or mechanized agricultural vehicle … when circumvention is a necessary step undertaken by the authorized owner of the vehicle to allow the diagnosis, repair, or lawful modification of a vehicle function."

This means modification of embedded software is legal long as it can still meet emission requirements. Whether the exemption allows for the downloading of cracked software is an unanswered question.

It's no surprise, then, that John Deere started requiring farmers to sign licensing agreements around the time the exemption went into effect. Violation of the agreement would be considered a breach of contract rather than a federal copyright violation, meaning John Deere would have to sue its own customers if it wants the contract to be enforced. I asked John Deere specifically about the fact that a software black market has cropped up for its tractors, but the company instead said that there are no repair problems for John Deere customers.

"When a customer buys John Deere equipment, he or she owns the equipment," the company said. "As the owner, he or she has the ability to maintain and repair the equipment. The customer also has the ability through operator and service manuals and other resources to enable operational, maintenance, service and diagnostics activities to repair and maintain equipment."

"Software modifications increase the risk that equipment will not function as designed," the company continued. "As a result, allowing unqualified individuals to modify equipment software can endanger machine performance, in addition to Deere customers, dealers and others, resulting in equipment that no longer complies with industry and safety/environmental regulations."

Gay Gordon-Byrne, executive director of Repair.org, a trade organization fighting for right-to-repair legislation, told me that John Deere's statement is "total crap," and noted that "some of our members have repeatedly attempted to buy the diagnostics that are referenced [from John Deere] and been rebuffed."

"They require buyers to accept an End User License Agreement that disallows all of the activities they say are allowed in their statement," she said. "Deere is a monopolist and has systematically taken over the role of equipment owner, despite having been paid fairly and fully for equipment. Their claims to control equipment post-purchase are inconsistent with all aspects of ownership including accounting, taxation, and transfer of products into the secondary market."

It's quite simple, really. John Deere sold farmers their tractors, but has used software to maintain control of every aspect of its use after the sale. Kluthe, for example, uses pig manure to power his tractor, which requires engine modifications that would likely violate John Deere's terms of service on newer machines.

"I take the hog waste and run it through an anaerobic digester and I've learned to compress the methane," he said. "I run an 80 percent methane in my Chevy Diesel Pickup and I run 90 percent methane in my tractor. And they both purr. I take a lot of pride in working on my equipment."

Farmers worry what will happen if John Deere is bought by another company, or what will happen if the company decides to stop servicing its tractors. And so they have taken matters into their own hands by taking control of the software themselves.

"What happens in 20 years when there's a new tractor out and John Deere doesn't want to fix these anymore?" the farmer using Ukrainian software told me. "Are we supposed to throw the tractor in the garbage, or what?"

Boing Boing

John Deere has turned itself into the poster-child for the DMCA, fighting farmers who say they want to fix their own tractors and access their data by saying that doing so violates the 1998 law's prohibition on bypassing copyright locks.

Deere's just reiterated that position to a US Copyright Office inquiry on the future of the law, joined by auto manufacturers (but not Tesla) and many other giant corporations, all of them arguing that since the gadgets you buy have software, and since that software is licensed, not sold, you don't really own any of that stuff. You are a licensee, and you have to use the gadget according to the license terms, which spell out where you have to buy your service, parts, consumables, apps, and so on.

As software eats the world, it's devouring the idea of private property -- "that sole and despotic dominion which one man claims and exercises over the external things of the world, in total exclusion of the right of any other individual in the universe."

The fact that the DMCA felonizes bypassing copyright locks, combined with the proliferation of copyrighted software in gadgets means that companies can turn their commercial preferences into private laws. Just design your gadget so that using is in any way apart from the official, prescribed way requires breaking a copyright lock. Now, anyone who violates your license terms is also committing a felony, punishable by five years in prison and a $500,000 fine.

For a first offense.

What's more, security researchers who reveal defects in these gadgets face the same harsh punishment, and routinely self-censor, even when they find potentially life-threatening bugs in medical implants or cars.

Other automakers pointed out that owners who make unsanctioned modifications could alter their vehicles in bad ways. They could tweak them to go faster. Or change engine parameters to run afoul of emissions regulations.

They’re right. That could happen. But those activities are (1) already illegal, and (2) have nothing to do with copyright. If you’re going too fast, a cop should stop you—copyright law shouldn’t. If you’re dodging emissions regulations, you should pay EPA fines—not DMCA fines. And the specter of someone doing something illegal shouldn’t justify shutting down all the reasonable and legal modifications people can make to the things they paid for.

GM went so far as to argue locking people out helps innovation. That’s like saying locking up books will inspire kids to be innovative writers, because they won’t be tempted to copy passages from a Hemingway novel. Meanwhile, outside of Bizarroland, actual technology experts—including the Electronic Frontier Foundation—have consistently labeled the DMCA an innovation killer. They insist that, rather than stopping content pirates, language in the DMCA has been used to stifle competition and expand corporate control over the life (and afterlife) of products.

0 comments:

Post a Comment