Eric Paley reports in Tech Crunch:

Entrepreneurs often say that they’re willing to take less personal financial gain for the chance to build a well-known brand. The reality is that this is rarely the tradeoff offered. The more common exit is not a multi-billion dollar IPO, but the high probability choice overcapitalized companies face is a decision to to take $50M and fail to clear your venture investor preference stack, or face bankruptcy and lay off your team.Taking capital too soon, and with too much dilution, has ripple effects beyond eventual payouts.

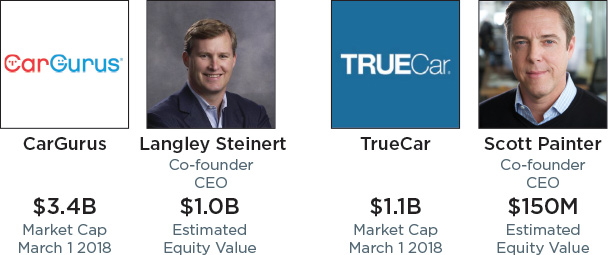

I’ve written a lot about the benefits of efficient entrepreneurship. I’ve explained my view conceptually, tried to illustrate the mechanics of how excess capital kills promising companies, and shared data from 71 IPOs that demonstrates that even in success, more capital raised is not correlated with better outcomes. Just in case all of that was too conceptual, this blog post is designed to appeal to another emotion—greed.Raising less money or money later doesn’t just lead to better companies, it leads to richer founders.Would You Rather Be the Founder of Zappos or Wayfair?I regularly ask MBA students at Harvard Business School, by a show of hands, would they have rather founded Zappos or Wayfair? All of the students know Zappos as a success story. Many haven’t even heard of Wayfair. Nine out of 10 of these savvy students choose Zappos.Zappos is a textbook success story. They raised staged, smart money from the best VCs in Silicon Valley. Founder Tony Hsieh’s unorthodox approach to leadership earned him magazine covers and a book deal. When the company was purchased by Amazon for somewhere between $850M and $1.2B, Hsieh walked away with somewhere between $214-367M. This is an extraordinary sum – A great success that makes Zappos a model that founders should study.But there are even better ecommerce startup stories that few founders know to study.Contrast Zappos with Wayfair, an ecommerce company that dropships furniture. The founders, Niraj Shah and Steve Conine bootstrapped the business and grew rapidly by optimizing against Google’s algorithm, buying up hundreds of SEO friendly URLs like “www.racksandstands.com” and agglomerating the traffic. The company was profitable from the first month and, despite many VC offers, they grew the business without outside capital until they had over $500M in sales. Some might view the company as solid, stable, and a little bit boring, but the founders were laughing all the way to their IPO on the NYSE in 2014. Among numerous remarkable attributes about the company is the financial success of the founders.Each of the founders owned ~29% of the company at the time of the IPO. Though they’ve regularly sold shares since, based on the company’s current $6.9B market cap EACH ONE of Wayfair’s two co-founders made as much money as ALL of Zappos’ shareholders combined. Put another way, by building an exceptional capital efficient business and only raising money when the company was already very valuable, Wayfair co-founder made at nearly 10X as much as Hsieh. I’d rather be Shah and Conine.Minimize Capital EarlyYou might say this discrepancy has to do with the relative size of the furniture and shoe markets. To be fair, the furniture business is approximately twice as large as the footwear market, though the shoe industry is arguably a better fit for ecommerce given the repeat nature of the customers, lower shipping costs, and much less friction for trial and return.While the industry dynamics likely play a role, I believe it’s the company’s capital strategies that made the difference. Wayfair didn’t raise money to start the company or to accelerate early growth, though it would have been easily available along the way; they only raised money when it was time to dramatically expand their business and invest in an already large and healthy company. They weren’t shy about taking on massive amounts of capital: Wayfair raised three times the capital that Zappos did, but only when it was minimally dilutive after the company’s dominance was established and could provide massive amounts of scale leverage.It’s Not All About the BenjaminsTaking capital too soon, and with too much dilution, has ripple effects beyond eventual payouts. After selling to Amazon, Hsieh suggested he was “forced” to sell the company due to pressure from his shareholders. Everyone involved made a fortune, but it is frustrating to subordinate your preferences based on financing decisions made half a decade earlier. If left in control of Zappos, Hsieh likely could have continued to grow his company and possibly even matched Wayfair’s success. The Wayfair founders owning more than half the company even at the IPO, and having raised money on their terms with limited dilution, were able to control their own destiny to a much greater degree and still run a phenomenal business today.TrueCar vs. CarGurusLet’s start again: by a show of hands, which public auto ecommerce company would you rather be – The founder of TrueCar or CarGurus? Decide before you look at the table below:

That’s right, with much less capital raised CarGurus is similarly profitable and growing much faster than TrueCar and therefore worth more than three times as much.

Because of the light capitalization of CarGurus, Langley Steinart owned 29% of the compan at the time of its IPO, a stake worth close to the entire value of TrueCar. At the time of the IPO, TrueCar founder Scott Painter owned ~14% of his company, an extraordinary amount to be sure, but this represents just a tenth of Steinert’s total value in CarGurus.Even in success, more capital does not make for better businesses and raising less money can pay off in multiples of personal wealth and control.These Are The Great OutcomesIn each of these examples, both companies succeeded and founders benefited with exceptional financial success. When I pose these thought experiments to entrepreneurs, they often push back and say that they’re willing to take less personal financial gain for the chance to build a well-known brand. They’re willing to forgo a billion-dollar bank account in favor of a mere hundred-million-dollar payday and fame. The reality is that this is rarely the tradeoff offered to founders.The more common exit opportunity is not a multi-billion dollar IPO, but a $50M-$100M acquisition. If you’ve raised a modest amount of money, that can be a transformative outcome. If you’ve raised tens of millions of dollars (or sometimes hundreds), many, if not all, of those exit opportunities will be closed. The high probability choice that overcapitalized companies face, is a decision to to take $50M and fail to clear your venture investor preference stack, or face bankruptcy and lay off your entire team. In either case, there is a good chance the founders see little or no return.A decade after their formation, Wayfair and CarGurus have become more valuable businesses than their counterparts and the founders benefited greatly from their lean financing strategies, but they’ve had something even more valuable along the way—optionality.Because they were never beholden to venture capitalists or outsize valuations, they had the flexibility to sell for $50M or $500M along the way. These founders could decide to sell, or not, depending on the performance of their businesses and appetite for risk, not their capital structure. There’s no shame in a $100M startup and founders shouldn’t be so quick to concede that option along the way.Even in success, too much capital has a high cost and shouldn’t be underestimated. Likewise, efficient entrepreneurship has many benefits that shouldn’t be underestimated. Just ask Niraj Shah, Steve Conine and Langley Steinert.

0 comments:

Post a Comment