But financialization sparked a series of owners who viewed it as a massive asset from which value could be plucked without reinvestment, let alone a competitive strategy. They sold off what they could, including the real estate, and let the rest to rot. Bankruptcy was the logical and - arguably the intended - end result of that strategy. JL

Steven Strahler reports in Crain's Chicago Business:

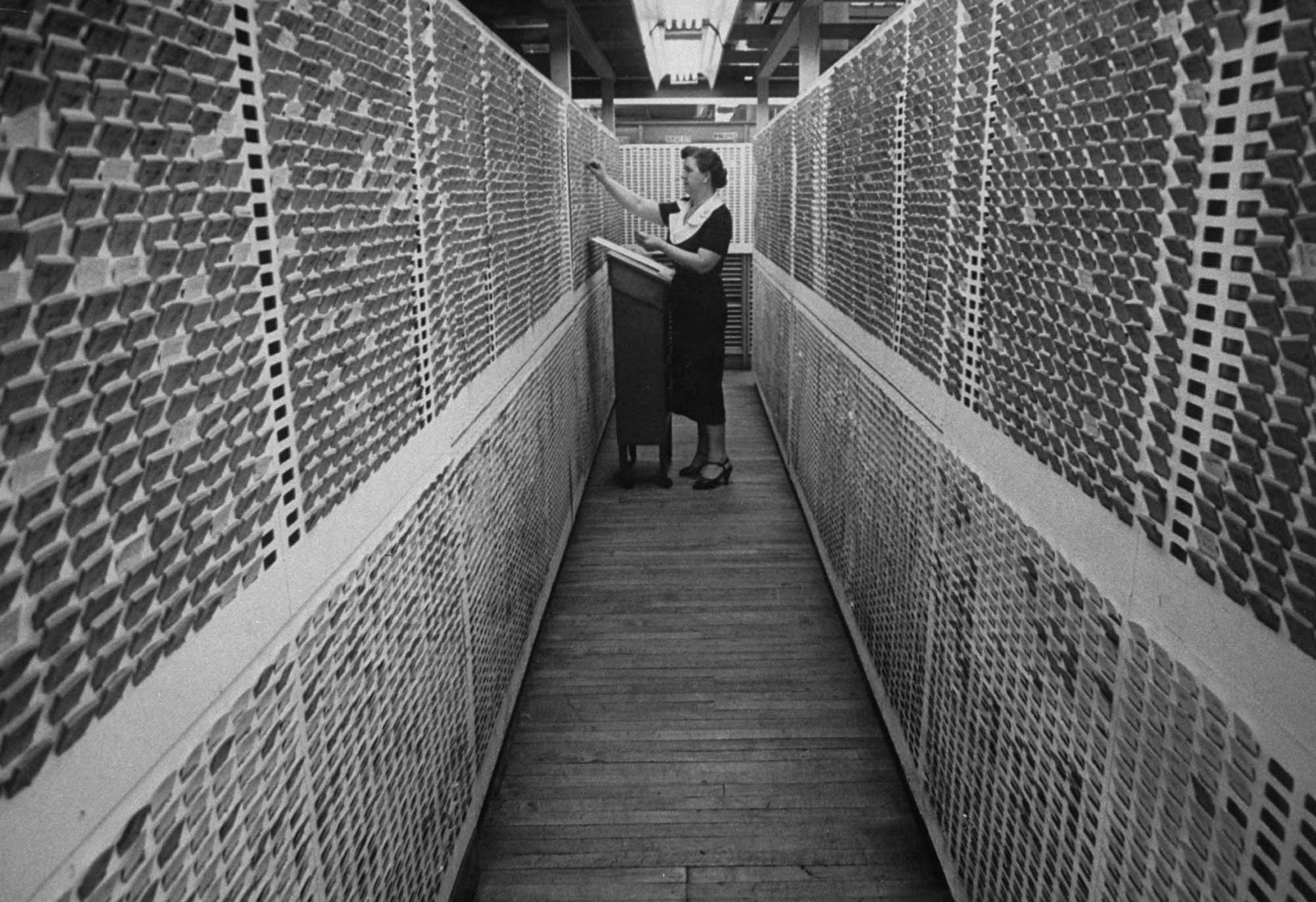

Sears (cut) thousands of locations and (sold) rights to brands like Allstate, Craftsman, Kenmore and DieHard. Profit came mainly from a Sears-branded MasterCard that let shoppers charge $20,000 anywhere, not just its own stores. Credit "was an important source of value creation, but also a source of loyalty that bound people to the stores. (Owner Lampert) believed he had the God-given talent to create a brand-new retail operating model, but he never articulated how his model was going to be any different. "He's going to preside over a slow liquidation of the company."Sears Holdings, the successor to Sears Roebuck, which revolutionized retailing at the turn of the 20th century and grew mighty as America suburbanized, is on its deathbed after a lengthy illness, filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. The 125-year-old company has been bleeding billions of dollars in cash for years.It's the latest and most prominent casualty in an old-line family of department stores instrumental in the rise of the shopping mall and, later, in their mutual decline. As its health failed, Sears' presence in its hometown of Chicago dwindled to a single store, which closed in April 2018.Sears had been confined to intensive care for years, kept on life support with hundreds of millions of dollars in loan transfusions from Edward Lampert, its controlling owner and CEO, and his hedge fund, ESL Investments. He stepped down as CEO with today's filing. In early October, the company added a restructuring expert to its board, even as $134 million in borrowings was about to come due—news that was shortly followed, ominously, by word that the company had hired a boutique corporate advisory firm to craft a bankruptcy filing that seemed imminent. It was a far cry from the healthier days, when Sears resided in a namesake Loop skyscraper whose status as the world's tallest building reflected the company's retail hegemony.Lampert was a Goldman Sachs alum lacking retail experience when he and ESL acquired Sears in 2005, using Kmart, seized in bankruptcy, to engineer a merger. He decided to pull the plug after promised synergies never materialized, and mounting debt and chronic underinvestment in stores led to losses this decade that topped $10 billion.Surgeons had prolonged Sears' life by amputating thousands of locations and selling or sacrificing rights to familiar brands like Craftsman, Kenmore and DieHard. The post-merger number of locations dwindled from 2,350 full-line stores to 842, as of September. But the hemorrhaging could not be stanched. Shoppers turned to Walmart and other giant discounters, to big-box appliance and electronics stores like Best Buy, and to home-improvement chains like Home Depot and Lowe's.By 1991, just before Sears left its tower, Walmart had displaced it as the nation's biggest retailer.Then came Amazon, whose disruption of 21st-century retailing has been compared to the upheaval Sears itself wrought when it perfected the mail-order catalog. Sears started building stores in the 1920s and shrewdly expanded in America's suburbs after World War II.Julius Rosenwald, architect of the transformation, "knew that Sears needed to be more than just a catalog house and (to) put up brick-and-mortar stores," said Peter Ascoli, his grandson and biographer. "He really understood what the future was going to be. Future leaders of Sears were not so prescient."Sears wasn't oblivious to the next retail revolution, but it was unable to capitalize on the rise of online shopping. Sears.com "didn't matter because people didn't want to engage with the brand," says Neil Stern, a retail consultant at Chicago's McMillan Doolittle.he end seemed near when Sears didn't advertise on TV during the 2017 holiday season—even as it brought back its once-beloved "Wish Book" after abandoning catalog publishing six years earlier—and same-store sales plunged 17 percent, while competitors' rose.Revenue had been halved in five years, to $22 billion. Walmart's had grown to 20 times that. As in other death spirals, suppliers threatened to cancel contracts and insisted on new payment terms. Sears sued two vendors in an effort to keep the goods coming.'STOCKS AND SOCKS'Sears survived several earlier heath scares. During the 1980s, as retail operations flagged, Sears diversified into financial services. It embarked on a "stocks and socks" strategy by acquiring broker Dean Witter Reynolds, real estate agency Coldwell Banker and charge card Discover, only to shed them in 1993. Next to go was insurer Allstate. By then, Sears was in a new suburban home after accepting tax subsidies to move its merchandise group and later its headquarters to Hoffman Estates. In 1994, it gave up ownership of the Sears Tower, having failed to find a buyer since 1988.For a while, retail operations revived under an apparel-focused "Softer Side of Sears" ad campaign. But profit came mainly from ballooning credit balances, thanks to a Sears-branded MasterCard that let shoppers charge as much as $20,000 anywhere, not just inside its own stores.Sears built a $30 billion loan portfolio but blinked and unloaded it in 2003 after other card issuers grew much bigger and regulators cracked down on the card industry.SALES SLIPArthur Martinez, a former Saks Fifth Avenue executive who became Sears' CEO in 1995, considered the sale a mistake. Credit "was not only an important source of value creation for the company, but also a critical source of loyalty that bound people to the stores," he told Crain's in 2012, 12 years after he departed the post. "When they lost that, they lost their customers."Arriving on the scene, Lampert was hailed in a 2004 BusinessWeek cover story as the next Warren Buffett. But unlike Buffett, who used faded textile maker Berkshire Hathaway to build a diversified investment portfolio, Lampert professed interest in reviving Sears and Kmart."I'm not from a retail background, but I am a shopper," he told Fortune magazine in 2006. "I come to this with practical, logical ideas."Lampert also differed from Buffett in other crucial respects: He lacked Buffett's folk-hero status and his hands-off tendency to target capable leaders and give them rein. When Lampert named himself CEO in 2013, he was Sears' fifth in seven years.nitially, investors bought his story: Sears Holdings stock, which began trading at about $13 in 2003 and hit $101 when the $11 billion Kmart deal was announced in late 2004, approached $200 in 2007. Share buybacks helped fuel the surge.FAILURE TO THRIVEBut when the financial crisis of 2008 and recession struck, Sears' revenue and earnings slumped, never to recover when the economy did. Profit disappeared for good after fiscal 2011, and store count continued to contract, from 3,510 to just over 1,000. In 2008, Lampert had tried retail engineering by reorganizing Sears into separate units, causing Bloomberg to comment in 2013, "Lampert runs Sears like a hedge-fund portfolio, with dozens of autonomous businesses competing for his attention and money." He also launched a rewards program called Shop Your Way that allowed Sears customers to earn points redeemable with Uber and other businesses.Consultant Stern believes Lampert thought he could energize the business, in part by stocking Kmart locations with Sears products and shrinking to a sustainable base through an "intelligent" loss of sales. Instead, "he's found out there's been no floor." Getty ImagesA worker in Sears Roebuck catalog office goes over files."There were no synergies with Kmart—just more zeros for financial engineering," adds Van Conway, another retail expert, based near Kmart's former headquarters in suburban Detroit.Sears spun off Orchard Hardware Stores in 2011 and divested Sears Hometown & Outlet Stores in 2012. A year later Lands' End, acquired in 2002, was spun off.A real estate investment trust created in 2015, Seritage Growth Properties, swallowed 258 Sears locations, initially raising $2.7 billion for Sears while stirring investor litigation. Plaintiffs alleged a conflict of interest because Lampert controlled both entities.In 2017, Sears sold the Craftsman line of tools to Stanley Black & Decker for about $900 million, discontinued sales of Whirlpool appliances and gave up exclusive rights to market Kenmore and DieHard. It won agreement to sell 140 stores to finance pension obligations. Sears Canada was liquidated.After a $2.2 billion loss in fiscal 2017, Sears faced reality: "Our historical operating results indicate substantial doubt exists related to the company's ability to continue as a going concern," it said in its annual report.Bruce Berkowitz, Sears' second-largest shareholder, named a director in 2016, quit in late 2017 and cut his Fairholme Capital Management stake from about 30 percent to 20 percent.A few months later, ESL lent Sears $100 million, at a rate of 12.5 points above the Libor benchmark, raising Lampert's Sears exposure to $1.16 billion, according to Bloomberg. With $1.5 billion in debt coming due, Lampert in a January 2018 blog post said Sears "will consider all other options to maximize the value of Sears Holdings' assets."

Getty ImagesA worker in Sears Roebuck catalog office goes over files."There were no synergies with Kmart—just more zeros for financial engineering," adds Van Conway, another retail expert, based near Kmart's former headquarters in suburban Detroit.Sears spun off Orchard Hardware Stores in 2011 and divested Sears Hometown & Outlet Stores in 2012. A year later Lands' End, acquired in 2002, was spun off.A real estate investment trust created in 2015, Seritage Growth Properties, swallowed 258 Sears locations, initially raising $2.7 billion for Sears while stirring investor litigation. Plaintiffs alleged a conflict of interest because Lampert controlled both entities.In 2017, Sears sold the Craftsman line of tools to Stanley Black & Decker for about $900 million, discontinued sales of Whirlpool appliances and gave up exclusive rights to market Kenmore and DieHard. It won agreement to sell 140 stores to finance pension obligations. Sears Canada was liquidated.After a $2.2 billion loss in fiscal 2017, Sears faced reality: "Our historical operating results indicate substantial doubt exists related to the company's ability to continue as a going concern," it said in its annual report.Bruce Berkowitz, Sears' second-largest shareholder, named a director in 2016, quit in late 2017 and cut his Fairholme Capital Management stake from about 30 percent to 20 percent.A few months later, ESL lent Sears $100 million, at a rate of 12.5 points above the Libor benchmark, raising Lampert's Sears exposure to $1.16 billion, according to Bloomberg. With $1.5 billion in debt coming due, Lampert in a January 2018 blog post said Sears "will consider all other options to maximize the value of Sears Holdings' assets." Getty ImagesShoppers walk into Sears store in a mall, circa 1983.The list of department store survivors, many in ill health, includes Target, Macy's, J.C. Penney, Nordstrom and Kohl's.Peers that didn't survive: Carson Pirie Scott, Montgomery Ward, Marshall Field's, Goldblatt's and Wieboldt's.In the 2012 Crain's interview, Martinez said of Lampert, "I believe that he believed at the time (of the merger) that he had the God-given talent to create a brand-new retail operating model, but he never articulated how his model was going to be any different." Martinez predicted, "Sears is past the tipping point. He's going to preside over a slow liquidation of the company."Lampert did deliver on one count. At Sears' 2010 annual meeting, he said, "Five years from now, I believe this company, to some people, will be unrecognizable to what it was 30 years ago."

Getty ImagesShoppers walk into Sears store in a mall, circa 1983.The list of department store survivors, many in ill health, includes Target, Macy's, J.C. Penney, Nordstrom and Kohl's.Peers that didn't survive: Carson Pirie Scott, Montgomery Ward, Marshall Field's, Goldblatt's and Wieboldt's.In the 2012 Crain's interview, Martinez said of Lampert, "I believe that he believed at the time (of the merger) that he had the God-given talent to create a brand-new retail operating model, but he never articulated how his model was going to be any different." Martinez predicted, "Sears is past the tipping point. He's going to preside over a slow liquidation of the company."Lampert did deliver on one count. At Sears' 2010 annual meeting, he said, "Five years from now, I believe this company, to some people, will be unrecognizable to what it was 30 years ago."

0 comments:

Post a Comment