WeWork has turned office space - the most fixed of fixed costs - into a variable cost for companies anticipating a recession - and it has no significant competition. JL

Ben Thompson reports in Stratechery:

WeWork is claiming every desk job around the globe as its market and doesn’t have competition. (It) seized the opportunity presented by unlimited capital to be the office of choice, intermediating and commoditizing traditional landlords.There is nothing more fixed than real estate, yet WeWork transforms real estate into a variable cost, with benefits that mirror public clouds. Common space shared by WeWork members can be built out more than any one member could build out on their own. Just as Amazon needed to build out data centers and buy servers before it could sell storage, WeWork needs to build out offices spaces before it can sell desktops.The bear case is unlimited capital has resulted in a complete lack of accountability.

The AWS Example

Imagine it is 2006, and you go to investors with a bold new business plan: computer hardware! Never mind that IBM just sold its PC business to Lenovo a year previously, and that servers appeared on the same path to commoditization, particularly with the emergence of x86 solutions from companies like Dell in place of specialized architectures from traditional suppliers like Sun. It doesn’t sound particularly promising.

And yet 2006 was the year that Amazon launched Amazon Web Services, a computer hardware business that leveraged the commoditization of hardware into a business with operating margins of around 30%. It turned out having one company manage that commodity hardware for everyone else had several important advantages that more than justified those margins:

In all three cases the fundamental shift was from servers as capital investment to variable costs; the benefits were less about saving dollars and cents and more about increasing flexibility and optionality. At least, that is, to start: today AWS has offerings that extend far beyond basic compute and storage to capabilities like server-less (which, paradoxically, requires owning an huge number of always-available servers) that are uniquely possible because of AWS’ scale.

- New companies had instant access to an entire server stack for basically free, because payments tracked usage (which for new companies is zero).

- Growing companies did not need to obtain funding for or spend the time on extensive build-outs months or years ahead of future growth, instead they could pay for new capabilities as they needed them.

- Established companies no longer needed to have a competency in managing server installations, and could instead focus on their core competencies while outsourcing to cloud providers.

The WeWork Bull Case

AWS, broadly speaking, is the WeWork bull case. Consider the phrase, “fixed cost”. There is nothing more fixed than real estate, yet WeWork’s offering transforms real estate into a variable cost for all kinds of companies, with benefits that roughly mirror public clouds:

Note that, just like the public cloud, price is not necessarily the primary driver for WeWork space. Still, there is no doubt that AWS, for example, pays far less for AWS’ underlying infrastructure than any of their customers would pay on their own. For one, AWS can spread the cost of data centers around the world over a huge number of customers; for another AWS can bargain with hardware suppliers or simply design and make its own components.

- New companies can have instant access to a well-appointed office space and pay for only a desk or two, and then grow as needed.

- Growing companies do not need to spend time on extensive build-outs months or years ahead of future growth, and instead pay for more space as they need it.

- Established companies no longer need to have a real estate competency all over the world, and can in fact expand to new territories with far less risk than previously required.

WeWork can achieve similar gains, to an extent. Within a single location, common space, by virtue of being shared by all WeWork members, can be built out much more than any one member could build out on their own. Similarly, WeWork’s network of locations around the world provide options that accrue to all members.

WeWork has also developed an expertise in utilizing office space efficiently, and while some of this is simply a willingness to cram more people into less space, opening triple-digit locations a year means that the company is by definition learning and iterating on what works for office space far faster than anyone else, and that is before the promised application of sensors and machine learning to the challenge.

And then there is the question as to whether WeWork is, or can become, more than a real estate play at scale: what might be the equivalent of “server-less” when it comes to office space — a unique capability that is uniquely unlocked by one company providing all of the real estate needs for, well, everyone?

WeWork’s Losses and Ambition

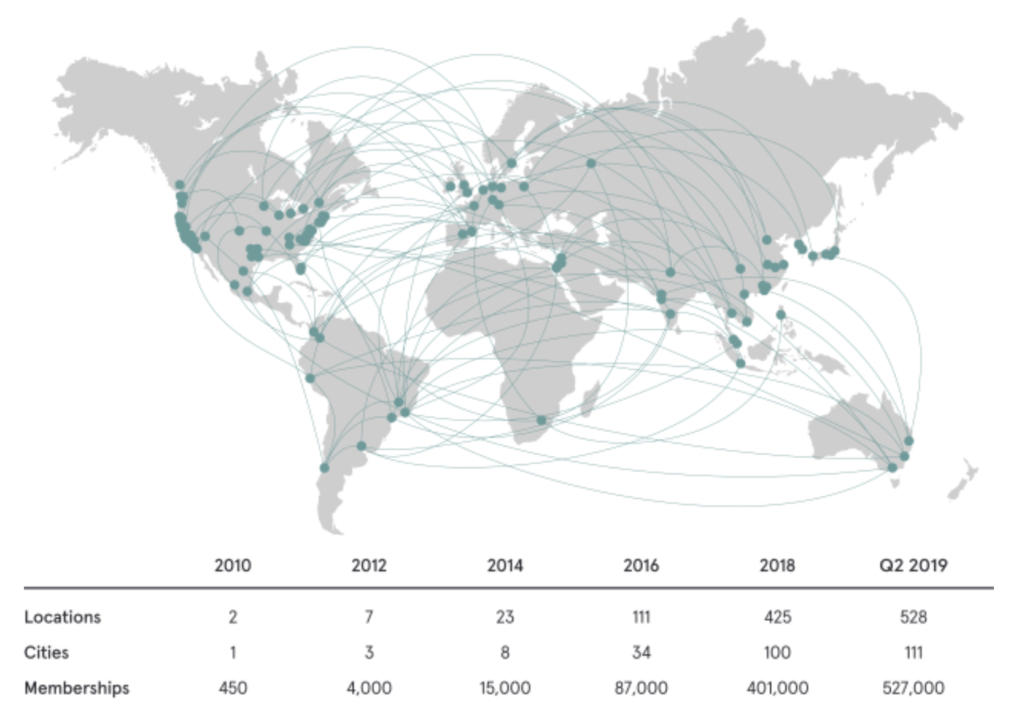

Given this vision, WeWork’s massive losses are, at least in theory, justifiable. The implication of creating a company that absorbs all of the fixed costs in order to offer a variable cost service to other companies is massive amounts of up-front investment. Just as Amazon needed to first build out data centers and buy servers before it could sell storage and compute, WeWork needs to build out offices spaces before it can sell desktops or conference rooms. In other words, it would be strange if WeWork were not losing lots of money, particularly given its expansion rate; from the S-1:

The company also includes this graphic, which on its own isn’t particularly helpful given the missing Y-axis:

What is useful is considering these two graphics together: over 300 locations — more than half — are in the money-losing part of the second graph, which helps explain why WeWork’s expenses are nearly double its revenue; should the company stop opening locations, it seems reasonable to expect that gap to close rapidly.

Still, it is doubtful that WeWork will slow the rate with which it opens locations given the company’s view of its total addressable market. From the S-1:

In the 111 cities in which we had locations as of June 1, 2019, we estimate that there are approximately 149 million potential members. For U.S. cities, we define potential members by the estimated number of desk jobs based on data from the Statistics of U.S. Businesses survey by the U.S. Census Bureau. For non-U.S. cities, we consider anyone in select occupations defined by the International Labor Organization — including managers, professionals, technicians and associate professionals and clerical support workers — to be potential members, because we assume that these individuals need workspace in which they have access to a desk and other services. We view this as our addressable market because of the broad variety of professions and industries among our members, the breadth of our solutions available to individuals and organizations of different types and our track record of developing new solutions in response to our members’ needs.Did you catch that? WeWork is claiming nearly every desk job around the globe as its market, a move that by definition means moving beyond being a real estate company. From the S-1:

We expect to expand aggressively in our existing cities as well as launch in up to 169 additional cities. We evaluate expansion in new cities based on multiple criteria, primarily our assessment of the potential member demand as well as the strategic value of having that city as part of our location portfolio. Based on data from Demographia and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, we have identified our market opportunity to be 280 target cities with an estimated potential member population of approximately 255 million people in aggregate.

When applying our average revenue per WeWork membership for the six months ended June 30, 2019 to our potential member population of 149 million people in our existing 111 cities, we estimate an addressable market opportunity of $945 billion. Among our total potential member population of approximately 255 million people across our 280 target cities globally, we estimate an addressable market opportunity of $1.6 trillion.

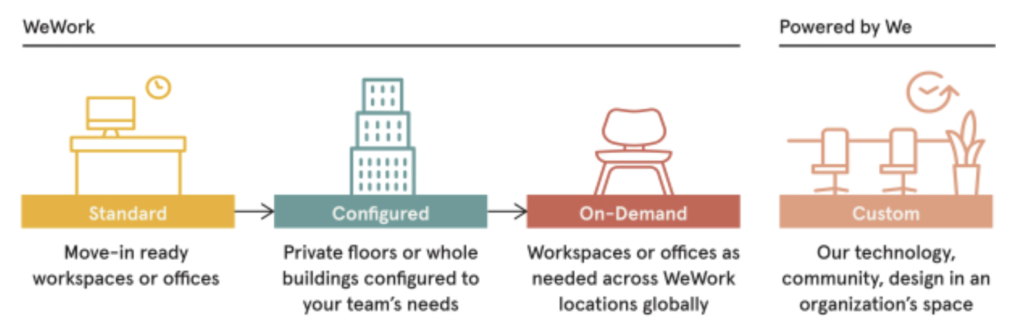

Our membership offerings are designed to accommodate our members’ distinct space needs. We provide standard, configured and on-demand memberships within our spaces. We also offer Powered by We, a premium solution configured to an organization’s needs and deployed at the organization’s location. Powered by We leverages our analysis, design and delivery capabilities to beautify and optimize an existing workplace, while also offering an organization increased efficiencies and an option to invigorate its spaces through our community offerings. The technology we deploy includes software and hardware solutions that deliver improved insights and an easier-to-use workplace experience for employees.The sheer scale of this ambition again calls back to AWS. It was in 2013 that Amazon’s management first stated that AWS could end up being the company’s biggest business; at that time AWS provided a mere 4% of Amazon’s revenue (but 33% of the profit). In 2018, though, AWS had grown by over 1000% and was up to 11% of Amazon’s revenue (and 59% of the profit), and that share is very much expected to grow, even as AWS faces a competitor in Microsoft Azure that is growing even faster, in large part because existing enterprises are moving to the cloud, not just startups.

WeWork, meanwhile, using its expansive definition of its addressable market, claims that it has realized only 0.2% of their total opportunity globally, and 0.6% of their opportunity in their ten largest cities. To be fair, one may be skeptical that existing enterprises in particular will be hesitant to turn over management of their existing offices to WeWork, which would dramatically curtail the opportunity; on the other hand, large enterprises now make up 40% of WeWork’s revenue (and rising), and more importantly, WeWork doesn’t have any significant competition.

WeWork’s (Lack of) Competition

This point around competition is an important one, and one of the more compelling reasons to be bullish on WeWork’s opportunity.

The obvious competitor is a company called IWG, with 3,306 locations and 445k workstations at the end of 2018. WeWork, in comparison, had 528 locations and 604k workstations as of June 30, 2019. Note the date mismatch — this isn’t a perfect comparison — but that only makes the point that these are two very different companies: WeWork had only 466k workstations at the end of 2018; a year earlier, when the Wall Street Journal pointed out that WeWork’s then-valuation was 5x IWG’s (it is now 13x), WeWork had a mere 150k, while IWG had 414k.

In other words, WeWork is massively more concentrated than IWG (i.e. fewer locations with more workstations), and growing exponentially faster; unsurprisingly, and relatedly, IWG is making money (£154 million last year). That, though, further makes the point: IWG, for better or worse, is constrained by the revenue it makes; WeWork, on the other hand, is perhaps best understood as a clear beneficiary of a world of seemingly unlimited capital. It is difficult to see IWG competing in the long run, or, frankly, anyone else: who is going to fund a WeWork competitor, instead of simply pouring more money into WeWork itself?

Capital and Recessions

This question of capital is perhaps the biggest one facing WeWork: from the company’s inception on critics have (fairly) wondered what will happen in a recession. It is one thing to sign long leases at low rates and rent out office space at higher rates when the economy is growing; what happens when the economy is shrinking and those long-term leases are not going anywhere, while WeWork customers very well may be?

This is a fair concern and almost certainly the largest reason to be skeptical of WeWork in the short run, but the company does have counter-arguments:

The company also has another, rather unsavory, advantage in a recession: its opaque corporate structure. While there are many downsides to the fact that the “We Company” is a collection of entities, one of the big advantages is that landlords will have a difficult time enforcing any leases that WeWork abandons. From the Financial Times:

- First, WeWork argues that in a downturn increased flexibility and lower costs (relative to traditional office space) may in fact attract new customers.

- Second, WeWork claims its growing enterprise customer base has nearly doubled lease commitments to 15 months with a committed revenue backlog of $4.0 billion; this is still far shorter than WeWork’s mostly 15-year leases, but perhaps long enough to stabilize the company through a recession.

- Third, WeWork notes that a recession — provided the company has sufficient capital — would actually allow it to accelerate its buildout as lease and construction costs come down.

There are limits to what landlords can do to enforce rental commitments. The company, like others in the shared office sector, creates special purpose vehicles for its leases, meaning landlords do not have direct recourse to the parent company if it fails to pay rent.Those guarantees are only $1.6 billion more than WeWork’s committed revenue backlog.

In the past, companies in the sector have changed the terms of their leases when downturns hit. Regus, now IWG, renegotiated leases in 2002 when the end of the tech boom cut into its customer base. More recently, an IWG subsidiary that leased a site near Heathrow airport applied for voluntary liquidation.

To counter such concerns, WeWork has guaranteed a portion of its rental payments, though a small fraction of the overall obligation. About $4.5bn of rent payments are backed by corporate guarantees and $1.1bn by bank guarantees, according to the group’s pre-IPO filing. It has paid more than $268.3m in cash deposits to landlords and used another $183.9m of surety bonds, a form of insurance.

WeWork’s Corporate Governance

Frankly, there is a lot to like about the WeWork opportunity. Yes, a $47 billion valuation seems way too high, particularly given the fact the company is on pace to make only about $440 million in gross profit this year (i.e. excluding all buildout and corporate costs), and given the huge recession risk. At the same time, this is a real business that provides real benefits to companies of all sizes, and those benefits are only growing as the nature of work changes to favor more office work generally and more remote work specifically. And, critically, there is no real competition.

The problem is that the “unsavoriness” I referred to above is hardly limited to the fact that WeWork can stiff its landlords in an emergency. The tech industry generally speaking is hardly a model for good corporate governance, but WeWork takes the absurdity an entirely different level. For example:

Byrne Hobart has made the case that some of the real estate transactions with Neumann are justifiable, but given how bad everything else in this list is, not assuming the worst is a generous interpretation; meanwhile, Neumann has already reportedly cashed out $700 million of his holdings via sales and loans. Everything taken together hints at a completely unaccountable executive looting a company that is running as quickly as it can from massive losses that may very well be fatal whenever the next recession hits.

- WeWork paid its own CEO, Adam Neumann, $5.9 million for the “We” trademark when the company reorganized itself earlier this year.

- That reorganization created a limited liability company to hold the assets; investors, however, will buy into a corporation that holds a share of the LLC, while other LLC partners hold the rest, reducing their tax burden.

- WeWork previously gave Neumann loans to buy properties that WeWork then rented.

- WeWork has hired several of Neumann’s relatives, and Neumann’s wife would be one of three members of a committee tasked to replace Neumann if he were to die or become permanently disabled over the next decade.

- Neumann has three different types of shares that guarantee him majority voting power; those shares retain their rights if sold or given away, instead of converting to common shares.

The Capital Glut

In fact, I would argue that the WeWork bull case and bear case have more in common than it seems: both are the logical conclusion of effectively unlimited capital. The bull case is that WeWork has seized the opportunity presented by that capital to make a credible play to be the office of choice for companies all over the world, effectively intermediating and commoditizing traditional landlords. It is utterly audacious, and for that reason free of competition. The bear case, meanwhile, is that unlimited capital has resulted in a complete lack of accountability and a predictable litany of abuses, both in terms of corporate risk-taking and personal rent-seeking.

Perhaps the real question, then, is what has driven the capital glut that has both helped WeWork’s business and harmed WeWork’s corporate governance? Is it merely the current economic cycle, which means a recession will not only pressure WeWork’s finances but also turn off the spigot of cash? Or has there been a fundamental shift in the global economy, as the increased impact of technology, with its capital-intensive business model that throws off huge amounts of cash, drives more and more global output?

In short, there is a case that WeWork is both a symptom of software-eating-the-world, as well as an enabler and driver of the same, which would mean the company would still have access to the capital it needs even in a recession. Investors would just have to accept the fact they will have absolutely no impact on how it is used, and that, beyond the sky-high valuation and the real concerns about a duration mismatch in a recession, is a very good reason to stay away.

1 comments:

budget car rental fort lauderdale fl, car rental hudson wi car rental hudson wi rental car hire

Post a Comment