Patrick Kulp reports in Ad Week:

As closing the loop between offline shopping behavior and online advertising has become a holy grail of sorts for digital advertisers, some retailers have zeroed in on weather-based marketing and consumer behavior as a key component. The extra level of granularity provided by private forecasts can come in handy for a brand to steer marketing messages.The private weather industry could grow fivefold as “attractive new product offerings” allow businesses to wring more cost savings and revenue growth out of weather information.

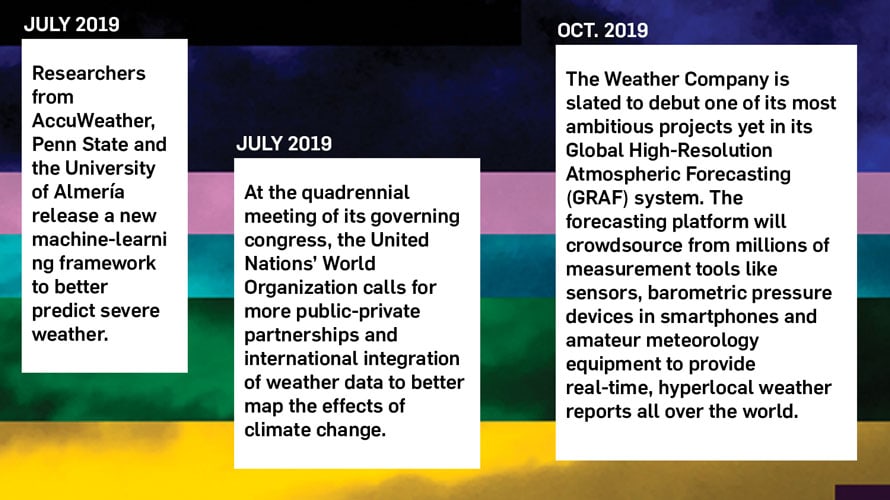

As tropical storm Dorian bore down on Puerto Rico last month, its whirling winds threatening to reach hurricane force, a team of Walmart employees watched closely from an array of screens at the retailer’s Arkansas headquarters 2,000 miles away.

Had the severity grown to crisis levels, Lucas McDonald, a former TV weatherman who leads the chain’s emergency operations, might have called in dozens of workers to support the handful who are posted at the division’s command center in 24/7 shifts. The full-house team—typically assembled only a few times a year—would help coordinate relief efforts, adjust supply routes and disseminate information to affected stores, a playbook the company has perfected through two exceptionally hectic hurricane seasons.

“Right now, we’re having conversations with some of our merchants on when the right time to ship more supplies into places like Florida and the Southeast would be ahead of any possible redevelopment from Dorian after it makes its way through Hispaniola,” McDonald says.

Meanwhile, in Dallas, meteorologists at Southwest Airlines mapped out contingency plans for rerouting and canceling flights given various possible hurricane scenarios. And in the Atlanta nerve center of IBM-owned Weather Company, forecasters relayed storm data and analysis to corporate clients like State Farm, which in turn used it to inform IBM Watson conversational ad units that spread safety information.

“It is all hands on deck,” says Kevin Petty, the Weather Company’s director of science, forecast operations and public-private partnerships. “We have meteorologists on staff talking to our clients to keep them up-to-date informed on the situation and how it might be changing, and how it might impact their operations.”

As data analytics technology and low-cost meteorological equipment have made reams of data more tractable, and climate change has upped the intensity, volatility and, thus, economic toll of extreme or erratic weather events, businesses are increasingly investing in operations like these to better monitor and shape operations around weather conditions.

While exact figures on this trend are hard to come by, a 2017 National Weather Service report estimated that the private weather industry could grow fivefold as “attractive new product offerings” allow businesses to wring more cost savings and revenue growth out of weather information. At the same time, Morgan Stanley estimates that climate-related disasters cost the global economy $650 billion in the last three years, a number that’s only expected to grow.

“What brands and businesses are really looking for now is how they get ahead of that, how they get the data and the insights to help mitigate that impact in advance,” says Randi Stipes, CMO of IBM Watson Media and the Weather Company. “More and more brands now are becoming savvy. They may even have weather operations and meteorologists on staff.”

Weatherman Watson

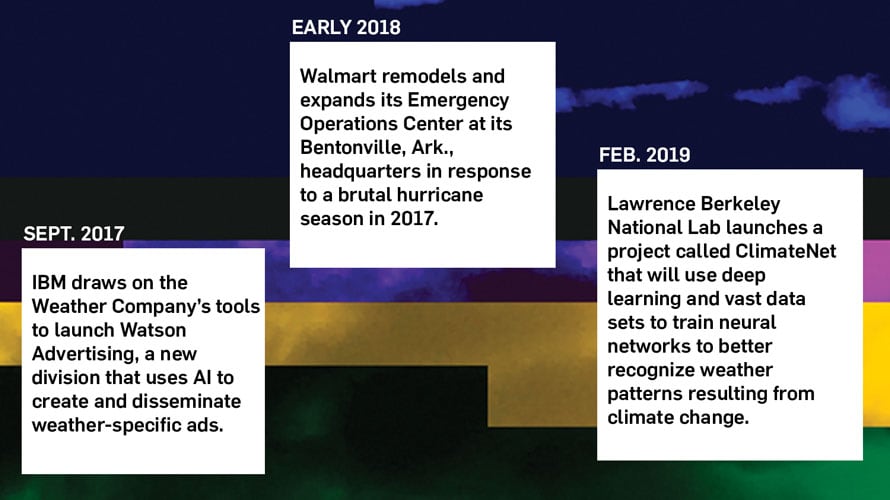

IBM has been one of the companies on the forefront of this trend since its acquisition of the Weather Company in 2015 for a reported $2 billion-plus. The deal was met with some confusion from industry watchers, who were at a loss to explain what the artificial-intelligence giant might want with the three-decades-old forecaster.

The company revealed an initial answer to that question the next year with the rollout of Deep Thunder, a hyperlocal forecasting platform that integrated machine learning to help retailers understand how granular weather changes could affect consumer buying behavior. Big Blue has also been working to integrate its Watson artificial intelligence platform with the forecasting giant’s data to power everything from weather-targeted ads to logistics coordination.

And now, IBM is poised to add another big piece to that puzzle next month with the release of its Global High-Resolution Atmospheric Forecasting (GRAF) system, an even more advanced hyperlocal forecasting tool that will pull data from millions of sensors in aircraft, barometric pressure meters built into smartphones (if the owner opts in) and even the equipment of amateur weather hobbyists. A back-end powered by the same hardware as the world’s most powerful supercomputers—the U.S. Department of Energy’s Summit and Sierra—will process that massive torrent of inputs, forming it into an hourly updating global forecast that IBM claims will provide double the clarity of existing models in most of the world.

“[India, Africa and the Middle East] are really underserved regions right now,” Petty says. “When you start providing accuracy at scales that have never been achieved before, it will change the way people make decisions.”

The Weather Company builds much of its domestic models around National Weather Service data, which still serves as the foundational underpinning of the current private weather industry boom. But as proprietary data-gathering systems grow cheaper and more advanced, critics worry that their growth will lead to the privatization of forecasting, closing off critical information from the nonpaying public.

The Weather Company insists that it works closely with public and academic institutional partners and that projects like GRAF are aimed at “democratizing” forecasts—especially in areas where governmental coverage isn’t as robust.

“We really believe in the democratization of weather—we believe in providing access to the most reliable and accurate weather data for everyone,” Stipes says. “Other countries across the planet haven’t had access to the level of accuracy and resolution and forecasting that we’ve come to appreciate and arguably take for granted in the United States.”

Rain or shop

The extra level of granularity provided by private forecasts can come in handy for a brand like air filter maker 3M Filtrete, which uses Weather Company data on pollen levels and the climate patterns that affect them to steer marketing messages. In doing so, the brand has traced regional behaviors around various types of pollen—from ragweed to tree borne—with more nuance than was previously possible when its marketers relied on analog sources like Farmers’ Almanacs.

“It’s really alleviated a lot of that manual work,” says Chris Luna, a consumer business group engagement leader at 3M. “It was a lot of, you know, turn it on, turn it off, pull it out—which region is being affected—turn on spend there, et cetera. We can now just do that dynamically.”

This sort of relationship between buying patterns and weather might sound intuitive in some ways—obviously, people are more likely to want ice cream when it’s hot out or a coat on a rainy day. But marketers who work in this field say there is a lot more complexity involved in these types of questions than one might expect.

When do New Yorkers want hot coffee? Oftentimes, they inexplicably gravitate to it when the weather is more humid, whereas Bostonians are more likely to sip espresso in the low-humidity rain, according to IBM’s research. When do Floridians buy theme park tickets? The deep-learning analytics firm Cognitiv was surprised to find that the answer was rainy days, perhaps when the attractions are free of crowds of tourists.

“There’s not always the most logical behavioral pattern that you think is going to happen,” says Cognitiv co-founder and CEO Jeremy Fain. “It’s easy enough for any coder to take the National Weather Service feed and figure out what temperature it is. But to figure out whether that actually feels cold or hot or the weather is ‘nice’ or ‘not nice’ is much harder, because those are relative features.”

As closing the loop between offline shopping behavior and online advertising has become a holy grail of sorts for digital advertisers, some retailers have zeroed in on weather-based marketing and consumer behavior as a key component.

When Walmart’s emergency operations team isn’t orchestrating hurricane relief, for instance, one of its functions is to study questions like “the right temperature and weather pattern to sell more steaks versus hamburgers, and all that stuff plays into it,” says McDonald. Home Depot taps its business-continuity experts to know when to stock emergency prep supplies ahead of natural disasters, and the retailer has experimented with weather-triggered ads.“[Retail clients] want to be able to trigger marketing messages and also timing based on location, based on weather condition and also based on historical information,” says Eric Danetz, global chief revenue officer at AccuWeather, which has provided tailored commercial forecasts to clients ranging from Lowe’s to Live Nation. “When it comes to weather triggering, that can be a commodity. But when you take a look at the way we do it, with aspects that are proprietary to AccuWeather, we’re looking at specific conditions and how that human is going to feel and react based on a number of different variables.”

This trend is a major attitudinal shift for retailers, whose execs have previously tended to reference weather only to excuse poor business performance.

“We’ve seen that paradigm shift completely,” says Jonathan Porter, a meteorologist who serves as vp of business services at AccuWeather. “It used to be that weather was something that was passive and it was more of an accepted excuse, but companies now realize that they are obligated to use enhanced predictive capabilities to be more proactive.”

AI in the sky

Some companies say, however, that outside of IBM Watson and AccuWeather, which partners with Microsoft Azure for many of its AI solutions, the next inflection point of this tech evolution—machine learning and AI—is still in early days.

Weather analytics firm Planalytics, whose clients have included Kohl’s, Rite Aid and Subway, is currently exploring how to integrate its proprietary technology into its customers’ own machine-learning environments. The company expects self-training systems to eventually expand what can be discerned from data exponentially—as previous analytics tools have already in the past three years—but it has a long road ahead of it. “I would say that it is bleeding edge at this point,” says Planalytics svp of customer success Adam Moyer.

Anuj Agrawal, CMO of commercial weather data provider Earth Networks, warns that some of the talk of “machine learning” he sees in the space is actually overhyped basic statistics rather than truly self-learning systems.

“[The realization of machine-learning tech] has been a little slower than I expected, and there’s been a lot of over-marketing—which, of course, being a marketing guy, I’m probably somewhat to blame also,” Agrawal says. “I haven’t seen a real practical use case. … I don’t think it’s as widespread as I would have expected seven or eight years ago.”

That’s not to discount how drastically weather forecasting and analysis technology has changed in recent years with the rise of cheap computer processing power, more available data and other tech advances.

Warren Qualley, senior manager of meteorology at Southwest Airlines, says divisions like his 10-person staff have shrunk in recent years as smarter computers require fewer human operators. The team of around 21 meteorologists Qualley managed at American Airlines a decade and a half ago has been reduced to a single employee, with the rest of the airline’s weather needs farmed out to the Weather Company.

Businesses now generally expect much more insight from weather forecasts. “Six or seven years ago, people cared about fleece, people cared about bottled water. Now people care about purple North Face fleece size large and 24 packs of store-brand bottled water,” says Moyer of Planalytics. “When I started here, 11 years ago, I could get through one analysis of one product per day. Now we can do 5,000 to 10,000 analyses per day.”

State Farm Insurance has found increased consumer engagement with conversational ads that use IBM’s natural language processing to provide disaster safety information from local community organizations, according to State Farm marketing director Sue Beigie. Each time one of those ads isn’t able to address a user question, the feedback is sent back into the system to help it train itself.

An uncertain future

Of course, the backdrop to all this activity is that global climate change is disrupting seasonal weather patterns and increasing the toll of disaster events. Previously conventional prediction methods no longer cut it in this uncertain, higher-stakes environment, says IBM’s Stipes.

“It used to be that there was a very defined hurricane season that we knew we could expect to see at the same time every year,” she says. “I think that’s why brands are turning more to us to leverage technology like weather effects, where we’re kind of doing that work for them behind the scenes and triggering advertising when conditions are right versus looking at a calendar and activating on a specific day.”

Those effects are only going to amplify in coming years, likely pushing the functionality of all this new forecasting technology to its limits. “We don’t only need to do a better job [with climate change research] where we are currently serving populations,” says the Weather Company’s Petty. “There are going to be changes spatially across the globe, and extremes that we will eventually see will now be in places where maybe those extremes were not felt or experienced in the past. And so we have to be able to be in a position to address how things are going to change globally, and then capture those extreme events so that our customers and clients can make well-informed, educated decisions at the scale that they’re operating on.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment