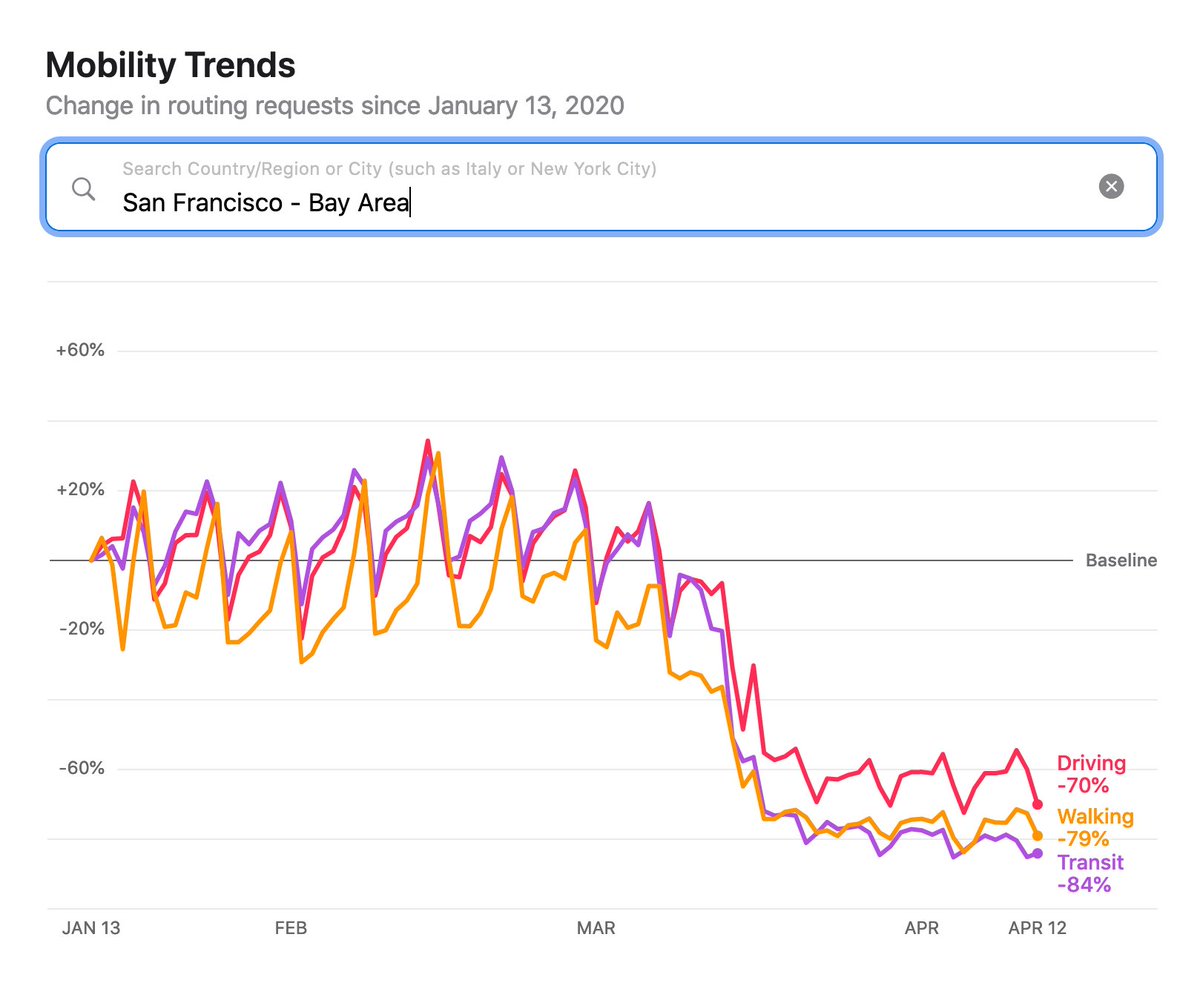

They suggest that people are traveling less. But it will be the correlation with infection rates data that provide the most useful information. JL

Cat Zakrzewski reports in the Washington Post:

A new tool that pulls data from its Maps service to help measure how effective social distancing measures are around the world. The tool tracks how driving, walking or public transit habits are changing based on their searches for directions to places. The data is presented in an anonymous, aggregated form, and officials can view it down to the city level. In Washington, requests for public transit directions declined 83% since January 13. Requests for walking directions were down 66%. Driving requests are down 56%.

Apple is the latest tech company to tap its troves of consumer data to help public officials fight the coronavirus.The company yesterday unveiled a new tool that pulls data from its Maps service to help officials measure how effective social distancing measures are around the world. The tool tracks how citizens' driving, walking or public transit habits are changing based on their searches for directions to places.The data is presented in an anonymous, aggregated form, and officials can view it down to the city level. For instance, it shows that in Washington, requests for public transit directions – for instance, by bus or subway – declined 83 percent since January 13. Even requests for walking directions were down 66 percent, suggesting that the restrictions are having a significant effect.

This tool can also compare the effects of social distancing between cities, or even between countries.Washington is increasingly looking to tech companies such as Apple as it seeks more data to understand whether social distancing policies are working – and make crucial decisions about how and when to re-open parts of the economy.But the companies are walking a fine line as they try to balance pressure from governments to take steps to maintain public health with their customers’ privacy expectations.This is a particularly delicate tightrope for Apple, which has made strong user privacy a central component to its marketing pitch.It's telling that Apple chief executive Tim Cook led with privacy when announcing the initiative:While protecting your privacy, we are sharing aggregated mobility data from Apple Maps to help public health authorities learn how people travel in their communities and to provide valuable insights to stop the spread of COVID-19. Stay safe and healthy! apple.com/newsroom/2020/…1,289 people are talking about thisApple says that the data isn't associated with any individual's Apple ID and that it doesn't keep a log of where you've been. Its data presents a birds-eye view of how people are moving – or at least, thinking about moving as they type in directions.This may not provide as much utility to public health officials as data that tracks their movements or presents what specific locations people are actually visiting within cities. And it's a far cry from the ways that other countries are using location data to map the spread of the virus. In South Korea, for instance, public officials have used cell phone location data to alert people if they’ve come in contact with the virus. In China, officials used their vast digital surveillance apparatus to monitor people’s movements and ensure they were abiding by quarantines.But as my colleague Geoffrey A. Fowler notes, it's still uncomfortable for Apple – a company that ran ads that say “what happens on your iPhone, stays on your iPhone” – to show how much data they're holding about consumers. And how it can be deployed for purposes people likely never imagined when they opened the app to find directions. From Fowler:Now Apple has covid-19 "Mobility Trends Reports,” too.

Wait, I thought Apple didn’t collect our data …

cc: @ReedAlbergottiapple.co/2XCsZPUApple says: "Maps doesn’t associate your data with your Apple ID, and Apple doesn’t keep a history of where you’ve been.”

But wait … doesn’t this chart mean Apple does have a history of where we’ve been?

“Unlike the idea of Bluetooth contact tracing, this doesn't raise privacy concerns because it can be conducted on an anonymous, aggregate sample and never requires re-identification or linkage,” he said.

0 comments:

Post a Comment