We're watching on a monitor, like a low-res version of a video game. When the tank image appears, the feeling in the 412th Nemesis Regiment command post is unfiltered hunter's excitement. To get one a UAV ready, the field team must remove already-mounted payloads, retrieve anti-armour munitions, and rearm the drone in the darkness. The Russian tank crew have ten minutes before a drone is hurtling towards them. The tank moves sluggishly along the wooded area – and then boom - the screen lights up with a bright white explosion. Every day these people destroy dozens of Russian vehicles and kill or maim hundreds of Russian soldiers. But it’s scrawny IT guys with cappuccinos on their desks. "It's like a version of The Matrix.""Look! Look, there's a tank!"

We’re at a command post of the 412th Nemesis Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Regiment, and a scout from the reconnaissance unit is pointing at a monitor on a nearby desk and gesticulating so wildly that he nearly jumps out of his seat.

And that's understandable: on the screen, a white rectangle is moving swiftly from the bottom left to the top right-hand corner.

"I'm telling you, it's definitely a tank! And that's the tank gun! No doubt about it," the soldier insists.

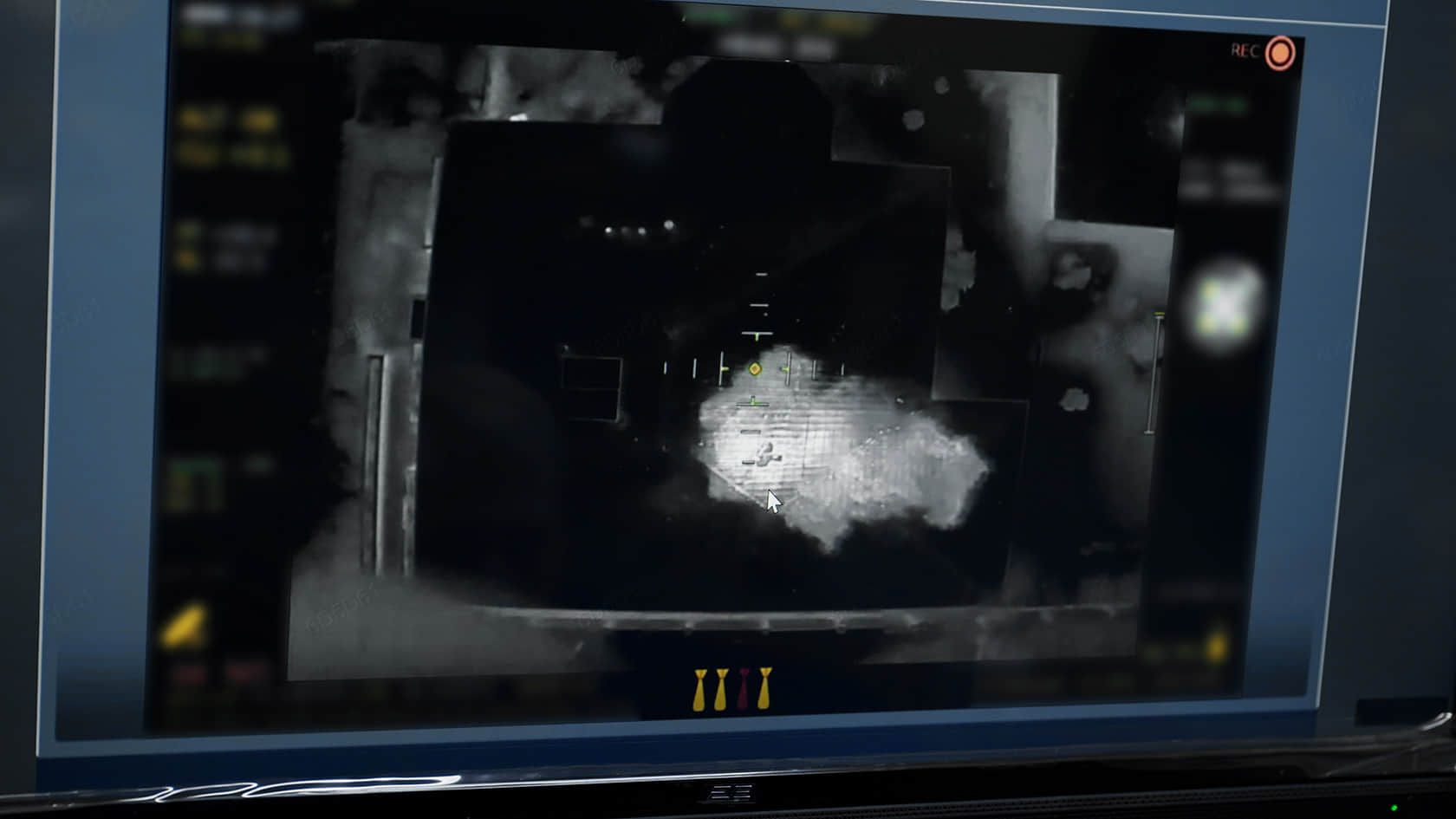

The black-and-white image from a night-vision drone camera, familiar to us all after over three years of war, comes into focus – and yes, a Russian tank is moving between a dark grey strip of wooded area and an almost pitch-black expanse of field.

"I'm telling you, it's a tank!" The target appears on the reconnaissance drone's live stream

Its gun is glowing bright white in the feed from a neighbouring unit. It’s still hot, meaning it recently targeted one of Ukraine’s defenders.

If we, the group at the command post – including reporters from Ukrainska Pravda – had been in that combat position or out in that field, the sight of the Russian tank would likely have filled us with dread.

But we're watching it on a monitor, like an old, low-res version of a tank video game. So when the image appears, the feeling that surges through the 412th Nemesis Regiment command post isn't fear or panic, but pure, unfiltered hunter's excitement.

"Take it! Tell them it's ours!" commands the chief of staff, aka Vito.

"Vito as in the Mercedes van?" we joked when he first told us his alias.

"No, no, as in Corleone," he replied with a good-natured laugh.

"Lazar's group [one of the most successful strike UAV units within the National Guard] is already there – they want to chase it too," reports a soldier from the planning team. He's tuned into a shared comms channel with fighters from other units along this sector of the Zaporizhzhia front.

"Tell them we've already claimed it! And get a drone in the air!" Vito is so fired up he’s practically shouting.

Of course, no drone is ready to launch at that moment.

To get one of the available UAVs ready, the field team must first remove the already-mounted payloads, retrieve anti-armour munitions from their vehicle, and hastily rearm the drone in the eerie darkness of the Ukrainian steppe.

"All set!" the planning soldier reports seven or eight minutes later.

"Let's go!" Vito says, and a conspiratorial grin spreads almost imperceptibly across every face in the room.

The drone still has some distance to cover. It's about 20 km away from the target. That means the Russian tank crew have another ten minutes before they'll even suspect that a heavily-armed hunter is hurtling towards them at full throttle on its four engines.

"Five more minutes and we'll be there," reports the soldier tracking the drone's path to the target.

Everyone watches calmly as the Russian tank moves sluggishly along the wooded area, passing a narrow junction of dirt roads – and then boom. The screen suddenly lights up with a bright white explosion. Even though there’s no sound on the recon drone's stream, everyone in the room instinctively flinches from the blast on screen.

"Looks like an FPV hit. Must be some of our infantry nearby," the soldiers say, trying to piece together what just happened.

"Someone hit our tank with an FPV drone," another soldier explains to someone else who's just come in from the kitchen or the toilet.

The Russian crew, unaware that their tank has now become "ours", charges off, full speed ahead – or rather, in reverse – towards their own positions.

The Nemesis drone dispatched to hit it hasn't even reached it yet, and now its team is facing a tough decision. The tank is pulling away from the line of contact at full throttle. If it had kept on crawling along, the drone could have got there, hit it and come back. But now the tank is gaining distance so fast that the drone may not have enough battery to make it back. This could end up being a one-way flight.

"They've decided to go after it," says the planning officer, somewhat concerned.

But after a few tense minutes, it becomes clear that we're not going to catch "our" tank. The Nemesis crew is forced to turn the drone around. It has less than 20% of its battery left.

* * *

"Not today then," Vito says with a smile, spreading his arms in a gesture of resignation after the failed tank strike. Then he adds pointedly, "When I first came to this sector, we were destroying air defence systems every other day. Now, seeing a tank here is like a special occasion. We've killed or injured so many Russian soldiers that spotting a tank within a 20-km radius has become an event – everyone wants to chase it."

"This sector" refers to the fairly broad stretch of the front, spanning several dozen kilometres, for which the tactical command post of the 412th Nemesis Regiment is responsible. The post is led by Vito himself.

In his past life, Vito had a humanities background and no combat experience, or even basic military training. But in the spring of 2024, he received his call-up notice and joined the armed forces. With his managerial experience from civilian life, Vito quickly became what you might call a "middle manager" in the military: he’s been entrusted with running a command post even though he hasn't yet received an officer's rank.

That in itself is something fairly unusual for the armed forces. But then again, the 412th Nemesis Regiment is a unit that only loosely resembles the old Ukrainian military.

It began as a battalion and has since grown into a regiment – a product of the drone war. Even now, there are probably senior commanders in the Armed Forces of Ukraine who struggle to understand how a regiment like this can function without any heavy equipment, with commanders walking around the command post in civvies, practically in their slippers.

But the 412th Nemesis Regiment, like other purely drone-based units, embodies the technological face of this war.

The Nemesis drone that gave the regiment its name is one of Ukraine's heavy bombers, a new class of UAV that has emerged in the course of the war.

But simply inventing and producing a drone like this wouldn't have been enough to make it a game-changer on the battlefield. Ukrainian soldiers and engineers have worked together to develop an entire strategy around how to use this type of weapon effectively.

* * *

As we were preparing for the nighttime operation during which the tank hunt described above took place, Vito agreed to give us a detailed explanation of how his tactical command post operates and how his unit fights in general.

"If we look at your regiment as a set of military functions, what is it made up of?" we ask Vito.

"Within the regiment, there are now units specialising in aerial reconnaissance, attack drones, signal interception, and surface drones," Vito explained."First we need to find out where the enemy equipment is located. To do that, we rely on reconnaissance. Everything is plotted on an electronic map. Then the planning stage begins.

We have certain strike capabilities, and we have the weather conditions, which unfortunately we have no control over, but they affect us… The guys plan the operation based on these parameters. And then the work begins.

Basically, everything is fairly simple. We have ground crews who go out into the fields to deploy the Nemesises. We have pilots who carry out the flights. And we have planning and reconnaissance, which synchronise everyone with each other, so to speak.

The analytics and planning section essentially oversees our entire area of responsibility. They see where [Russian] equipment is being concentrated, where artillery is arriving, what is changing along the line of contact. And accordingly, they determine where we need to respond as a priority.

We aren’t subordinate to the brigades along the front line, although we work closely with them. We’re constantly in contact with each brigade, we understand what’s going on with them, whether they need our support… And support is basically always needed – no one denies that.

There’s a fully centralised intelligence data system which gathers information from the brigades, from the central supply system and, of course, from our own aerial reconnaissance.

Now we're no longer a ‘mono-unit’ that only flies Nemesises. We have FPVs and strike wings as well now, we’re testing interceptor drones, for example – and much more. All of this involves different combat rhythms, different timeframes and different application practices that have to be integrated.

Yes, we’re quite widely dispersed. Thanks to the latest technology, drone operators can work at considerable distances from the line of contact.

That’s a huge advantage. A lot of our pilots are, let’s say, IT specialists who had no combat experience, and going right to the front line would have been pretty hard for them. But when you can apply the skills from your previous life, so to speak, with minimal risk, that has an impact on people’s motivation to serve with us.

So it’s an advantage for us, the fact that we’re decentralised and can involve people who aren’t ready to go straight to the contact line with a Kalashnikov.

And of course, there’s a huge difference between a pilot taking their first steps and a pilot who keeps doing more and more of the same tasks in safety. This way, we get far more capable pilots with minimal losses."

* * *

"Drop it! Tell him to drop and get out of there!" Vito, clearly alarmed, turns from the large screen to the planning team.

"The payload isn’t releasing. He’s dropping it, but it’s stuck," replies a soldier who is guiding a Nemesis drone toward one of the towns for the third time that night. The Russians, confident in their invulnerability, have set up a command post that is clearly at least battalion level in a mansion they have captured. During the day, many of them could be seen milling around, constantly loading up their vehicles with stuff, and they’ve installed checkpoints at the mansion’s entrance.

The fighters of the 412th have been monitoring this location for a long time, and tonight they finally have the chance to "take it apart". But the site, as if cursed, refuses to be dismantled.

The town is located right at the technical limit of the Nemesis's flight range, so the drone can’t loiter there for long. The first time, the soldier from the planning team, looking at the night feed, couldn’t find the house that had been filmed in the daytime reconnaissance. The drone circled around, waited, and had to return for new batteries.

The second flight was more successful – the Russians’ base was located – but due to unexpectedly strong wind and connectivity issues, it was impossible to precisely hit the same breach in the roof with multiple consecutive munitions, so no significant damage was caused.

Now a Nemesis is hovering over the target for the third time. It has only one specially prepared large munition left – one that, if it hits correctly, could blow the entire house apart. Two smaller bombs have already been dropped on a cluster of soldiers near the vehicles that had gathered between the second and third strikes.

The operator presses the drop button, but the munition refuses to release. When it finally does detach, it fails to hit the previously made breach in the roof. Some of the more emotional team members voice their frustration aloud.

"Oh well, at least the roof’s on fire. I want to see how they’re going to climb up there to get that munition out," someone more pragmatic quips.

"Well, they definitely won’t be living there. We torched a few vehicles. It’s fine. Worth doing. Though it is a shame," Vito sums up.

* * *

We came away from the 412th Nemesis Regiment command post with a twofold impression. On the one hand, it’s clear that this is a new kind of warfare – one where the ground crew that transport the drone to its position and the pilots who control it are located a thousand kilometres apart. The pilots and the ground fighters may have never even seen each other, even though they work together every day.

On the other hand, every day these people destroy dozens of Russian vehicles along the entire front line and kill or maim hundreds of Russian soldiers. But it’s not the hardened iron men so familiar to us from Soviet monuments who are doing this – it’s scrawny IT guys with cappuccinos on their desks, sitting in comfy leather chairs.

"When you think about where we are and what’s happening here, it’s like a version of the Matrix. You don’t come into contact with real live people or actual vehicles, or with wounded enemies or anything like that, but in reality, you’re destroying equipment and killing people on an industrial scale. How does that affect you? Do you feel involved in the war?" we ask Vito.

"Of course seeing a picture on a screen isn’t the same kind of war as going out to the front line, but actually our kind of war is pretty interactive in a way. Maybe that’s why the realisation hasn’t fully dawned yet. Right now, I don’t reflect much on what’s happening beyond the monitor. Maybe the time will come when there’s space to process it all, to think it through.

But we didn’t go to anyone else’s land. This land is ours. I’m definitely not some Rambo type who always dreamed of doing the things we have to do. We’re forced to do them. And this interactive war – well, it’s a challenge of modern times." The commander replies slowly, choosing almost every word with care. Then he sums up.

"But sometimes we do a job, and afterwards a spotter from one of the brigades appears on a livestream and says, 'Thanks, guys, the infantry really appreciated that.' And that’s when you realise you’ve helped real people and done something valuable for them. And to truly feel that, we try to go out into the field with the ground crew as well, so we don’t drift too far off 'into space'."

1 comments:

Cheap website design can be a cost-effective solution for startups, small businesses, or individuals working with limited budgets. It often provides the basic functionality needed to establish an online presence.

Post a Comment