The Red Army victory in WWII was enormous but was the product of the nation it was created to defend: cruel, corrupt and caring not a jot for the lives of its men. In Ukraine, despite having one of the largest militaries in the world, Russian forces have gained barely 20% of the country, have been invaded in turn and have suffered 900,000 casualties, as well as the loss of 10,000 tanks, 21,500 armored vehicles, 24,500 artillery and 370 aircraft. The key all Russia's wars is (in)comprehensible casualties. Anyone reading of (its sorry military history) – and high proportion of defeats - could think Russia is not very good at fighting wars. And they’d be right. The Red Army was sickeningly incompetent, as it is to this day. Putin, devoted to the legacy of the Great Patriotic War, has learned nothing.A question was sent into the WW2: We Have Ways of Making You Talk podcast the other day, asking whether the war in Ukraine would change the historiography of the Second World War. My co-host, Al Murray, and I thought about this briefly and agreed it probably would. Since then, I’ve been giving it quite a lot more thought and fascinating to consider it has been too. There’s a big narrative about the war on the Eastern Front, strongly adhered to by Vladimir Putin, that the Red Army almost single-handedly achieved victory against Nazism and that it was won, first and foremost, by Soviet blood. It’s not called the Great Patriotic War in Russia for nothing.

Over the last week or two I’ve been reconsidering the nature of the Soviet victory in World War II, but also the nature of the fighting during that conflict and, more broadly, Russia’s history of warfare since the turn of the twentieth century. It’s fair to say, the Second World War aside, Russia’s wars make for pretty sorry reading - if you’re Russian. They suffered an ignominious defeat at the hands of Japan in 1905, and which in large part led to the 1905 Russian revolution. Imperial Russia’s part in the subsequent First World War was a catastrophe leading to the loss of 5.5 million casualties, battlefield defeat and the overthrow of the Tsarist regime; the 1917 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk also saw Russia ceding large amounts of territory to Germany and its allies.

This was followed by the equally catastrophic civil war, which in turn led to war with Poland. This ended in further defeat and additional cessations of land in Ukraine and Belarus. There was then a pause until 1939 but during that time came the Stalinist purges in which some 22,000 Red Army officers were executed, including three out of five marshals, thirteen out of fifteen army commanders, fifty out of fifty-seven corps commanders, and 154 out of 186 army commanders. It was quite the cull and left the Red Army in a parlous state - so much so, in fact, that when it invaded tiny Finland in November 1939, it was once again badly humiliated. Finland was eventually forced to give up some territory in Karelia but retained its independence and inflicted disproportionately high casualties; while the Finns suffered up to 70,000 losses, the Red Army lost more than 350,000.

Parking World War II for a moment, there was bit-part and indirect involvement in the Korean War, the crushing of the Hungarian and Czechoslovakian uprisings in 1956 and 1968, and then the long ten-year Soviet-Afghan War, which, in 1989, led to yet another defeat. Russian forces eventually crushed resistance in Chechnya after another bloody ten-year long conflict from 1999-2009 and Georgia in 2008.

Which leads to Ukraine. Despite having one of the largest militaries in the world, and despite assuming Ukraine could be overrun in a matter of days, three years on, Russian forces have gained barely 20% of the country, have been invaded in turn and have suffered nearly 900,000 casualties, including over 300,000 dead, as well as the loss of more than 10,000 tanks, 21,500 armoured fighting vehicles, 41,000 vehicles, 24,500 artillery pieces and 370 aircraft. To put this in some perspective, 10,000 tank losses is a figure greater than the most heavily produced German tank of the entire Second World War. Clearly, the key feature of almost all these wars is barely comprehensible levels of casualties. Anyone reading this catalogue of death and destruction – and high proportion of defeats - could be forgiven for thinking that Russia is simply not very good at fighting wars. And they’d be right.

So, back to the Great Patriotic War, or perhaps it should be called ‘The Great Squandering War in Which the Capitalist West Saved the Soviet Union.’ Over the past twenty years, I’ve argued consistently that Nazi Germany was always unlikely to defeat the Soviet Union. In mid-June 1941, for example, Germany just had one enemy: Britain, albeit Britain plus empire and dominions. Fast forward six months to mid-December 1941 and Germany faced three enemies: Britain – plus empire and dominions, the USA and the USSR. I’ve always thought that the weight of manpower and materiel was simply too overwhelming for Germany to be able to prevail.

I still believe this, but I have come round to thinking it was a far closer-run thing in 1941-1942 than I had previously considered. It should not have been, however. The vast expanse of the Soviet Union, its immense natural assets, its often very difficult terrain, and the gross over-confidence of the invading German forces all worked against the invaders. So too did the total inadequacy of German logistics, lack of inter-operable parts, and the appalling self-defeating violence shown towards those especially in Ukraine and the Baltic States in the opening months of BARBAROSSA; the Germans also had woefully insufficient numbers of mechanized spearhead forces, while the senior commanders also had to deal with Hitler’s unwanted and unhelpful micromanagement. Collectively, this mitigated against a swift and decisive victory for Germany. They should never have had a chance, and yet they very nearly pulled it off.

That they did almost achieve a miraculous victory was more down to scarcely believable scales of Soviet incompetence rather than German brilliance. Stalin initially ignored all the very obvious warnings of invasion and was briefly a rabbit caught in headlights. He did quickly snap out of his panic-induced torpor, but his own micromanagement combined with the earlier purges led to a chronic lack of high-level command competence. The best part of three quarters of a million men were encircled at Kyiv in September 1941, for example, only because Stalin refused to allow his forces to retreat back across the River Dnipro.

Part of the narrative perpetrated by Stalin – and latterly Putin – is that the rapid relocation of Soviet industry from the western half of the Soviet Union back to the Urals saved the day and helped the Red Army win the war. While it is true that as many as 1,523 enterprises were packed up and shipped east in the summer of 1941, German forces still captured huge numbers of factories, mines and resources entirely intact. The capture of Zaporozhia and Tikhvin, for example, wrecked Soviet aluminium output and dramatically reduced tank production. Stalin was begging the Americans for aluminium as a consequence of these losses. The German capture of coalfields and steel production were equally catastrophic. Some 200 million tons of iron ore was lost, as well as 80,000 tons per month of manganese. Soviet war industry also lost 300,000 tons of coal per year as German forces swept eastwards as well as Ukraine’s grain.

The effects on the Soviet war machine were understandably terrible. Tank production, for example, went from 3,500 per month to just over 400. Total Soviet tank losses in 1941 alone were 22,340. That is not far off Germany’s entire tank production in the Second World War. Even in 1942, steel production was down to 8.8 million tons from 20 million in 1940. These were losses that went hand-in-glove with more than 4.5 million troops dead, wounded and in German captivity.

The Red Army did prevail outside Moscow in December 1941, but hardly convincingly. Marshal Zhukov told Stalin in November that year that he could hold Moscow if he had two more armies and a further 200 tanks. These reinforcements arrived because of British and American tank deliveries and because Stalin did everything he could to undermine a peaceful conclusion to the US-Japanese tensions building over the course of 1941. Intelligence that might have prevented Japan from escalating to war against the US was not passed on because he knew that if the Japanese began a series of operations southwards, he could safely move his armies on the Manchurian front westwards. What’s more despite claiming it was Soviet blood that was saving the west, he had actively helped Nazi Germany prosecute its war against Britain and France the previous year. The Luftwaffe was bombing Britain using Russian fuel. Up until the Germans launched BARBAROSSA, Stalin had actively worked against Britain, and even after the German invasion, he continued to undermine the Allies.

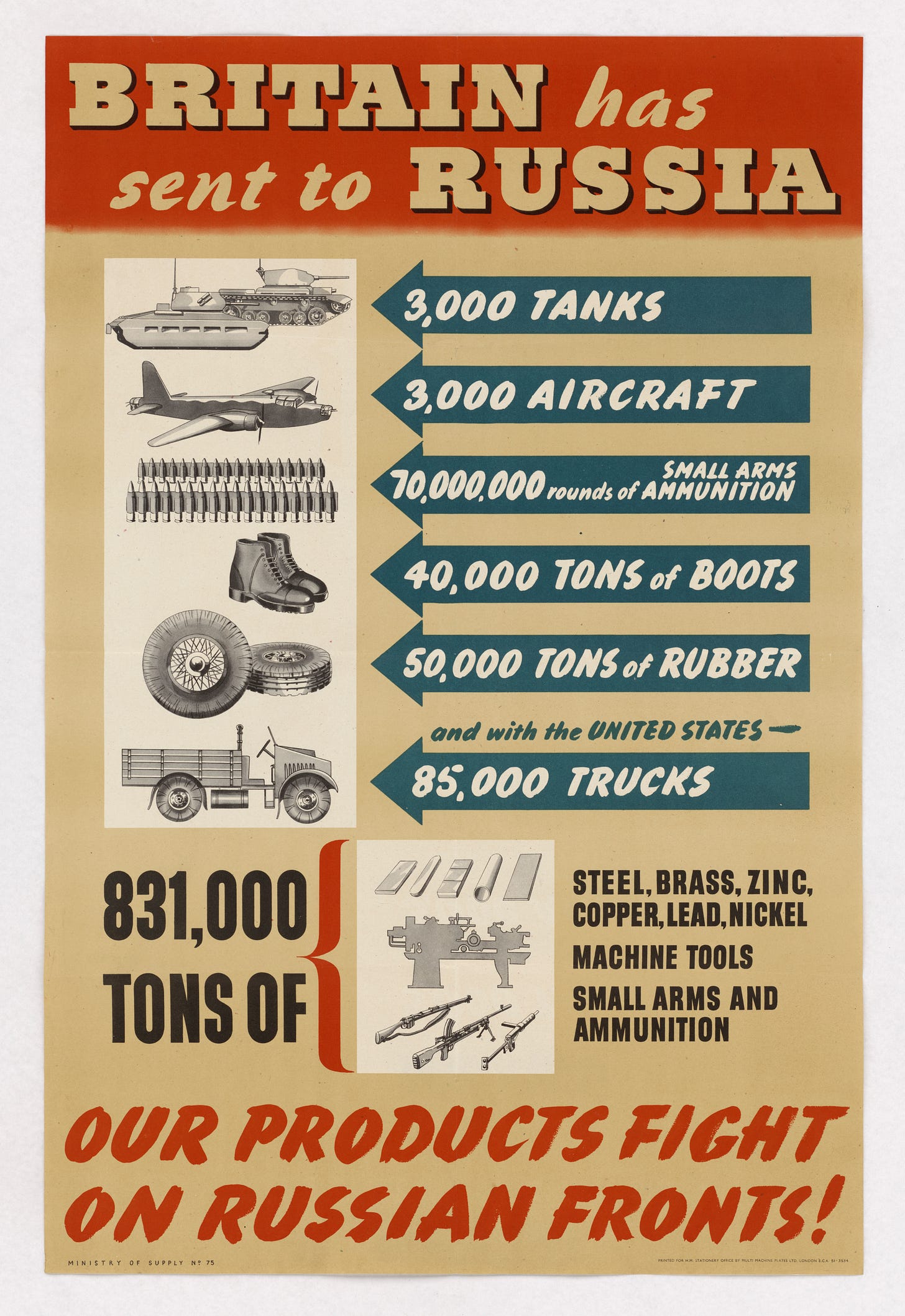

The scale of Lend Lease to the Soviet Union – and from both the USA and Britain – was astonishing. Tanks, guns, trucks, jeeps, aircraft, aluminium and a mass of other supplies kept the Soviet Union afloat as it desperately realigned its war factories in the Urals and continued to haemorrhage ever more troops. By the summer of 1942, the Americans had delivered 381,431 miles of telephone cable, more than fifteen times the circumference of the world. Stalingrad, the greatest of Soviet victories in the war, was only possible thanks to the generosity of the capitalists in the west. Red Army troops might have been doggedly fighting in the ruins of the wrecked city in the final months of 1942, but it was the encirclement beyond Stalingrad, from the north and south, that trapped the German Sixth Army and forced the great turning point in the war on the Eastern Front. Operation URANUS, as Zhukov’s encirclement was named, would not have been possible without 70,000 American trucks and jeeps, and half a million tons of US fuel and lubricants. Also taking part were a staggering 4,469 tanks and gun carriers and 1,663 Allied warplanes. ‘However impolite it may seem to some Russians to mention it, it is an imperishable fact,’ wrote the historian Sean McMeekin, ‘that Anglo-American capitalism helped win the battle of Stalingrad.’

As Germany burned itself out and Soviet factories recovered, so it became increasingly certain that the Red Army would win the Great Patriotic War after all. That Germany was becoming increasingly diminished was, of course, in no small part because of their fighting the Western Allies as well. There were always far greater number of troops on the Eastern Front than in Western Europe, but this should not be confused with strategic importance and had more to do with geographical scale. With the Axis surrender in Tunisia in May 1943, more troops were lost than at Stalingrad and considerably more materiel. And between June and October 1943, for example, the Luftwaffe lost 702 aircraft on the Eastern Front but 3,704 in the Mediterranean. The increasingly relentless air assault on the Reich was also hammering German industry and infrastructure and reducing its ability to do anything with much efficiency.

And this leads to the question of blood being spilled. It is absolutely the case that the Red Army lost considerably more lives than the Western Allies or even those of the Germans they were defeating, but this doesn’t mean it was taking on the greatest proportion of fighting. On the contrary, the Western Allies were fighting a truly global war on land, in the air and at sea, and overall taking on a far greater burden of Axis forces. Until the final months of the war against Japan, the Soviet Union was only fighting on the Eastern Front and spectacularly inefficiently too.

While the Western Allies very sensibly harnessed technology, global reach, mechanization and logistical deftness to limit the number of men risking their lives at the coal face of war, the Red Army continued its policy of barely imaginable profligacy. The Allies adopted a policy of ‘steel not flesh’ as far as they possibly could; the Soviet Union, on the other hand, pursued ‘steel in tandem with immense amounts of flesh’ and with terrible consequences.

The Soviet triumph at Stalingrad began the long road to victory that eventually ended in May 1945 on the banks of the River Elbe, seventy miles west of Berlin. New, more skilled commanders, did also claw their way to the top. Men like Ivan Konev and Konstantin Rokossovksy were brilliant – but utterly ruthless – generals, while the architect of the defence of Moscow and Operation URANUS, Marshal Georgy Zhukov, managed to keep on the right side of Stalin to the end; it was his men that eventually took Berlin after losses of 800,000 troops in two weeks in the second half of April 1945. New tactics were developed which became known as the ‘deep battle.’ The counter-attack at Kursk, the sweeping gains of Operation BAGRATION in the summer of 1944 and the subsequent capture of Poland and the Baltic States suggested the Red Army had become unstoppable. In a way, it had, but only because by then the material advantage over the Germans was so enormous. Forty-to-one in terms of tanks and artillery, and at least ten-to-one in manpower ensured there was one Red Army victory after another.

Deep battle meant pulling back a giant battering ram and then releasing it: overwhelming men, armour, guns and, crucially, support vehicles, all hurtled into the enemy with an almighty weight of violence and mayhem. The Germans had no answer but still, despite being on their knees, inflicted greater casualties on the Red Army than they suffered themselves. This ensured that while Soviet operations such as BAGRATION lasted eight weeks or so, they inevitably ran out of steam. While yet more divisions were hastily created and more tanks flowed off the production lines there was a natural pause. Then the battering ram was swung back again, with the same results.

Deep battle had become a war-winning strategy, but it was spectacularly careless and costly. Because of the horrific rate of casualties and the need to replenish swiftly, the men packed off for the next giant punch were invariably very badly trained. Their means of victory was purely by overwhelming weight of numbers. And in the end, it was also a victory that had been won thanks to the equally overwhelming amounts of Anglo-US materiel.

We have, in recent decades, been too generous to the Red Army. Their victory in the Second World War was enormous and the sacrifice immense. It should not have been so expensive in lives, however. Rather, the Red Army was very much the product of the nation it was created to defend: one that was cruel and corrupt and which cared not a jot for the lives of the men – and women – being flung into the fire. It was, for the most part, sickeningly incompetent, just as it still is to this day. Putin, so devoted to the legacy of the Great Patriotic War, has learned nothing.

May 1, 2025

Why Russia's Sad Military History Bodes Ill For It's Ukraine War Prospects

Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine with a decided reputational advantage: it had long claimed pride of place among the victors over the Nazis in WWII and was ruthless in subduing its weaker neighbors ever since.

But subsequent research has revealed that status to be substantially overblown. In fact, Russia has lost more wars than it has won and almost always with incomprehensible casualties. Its military in WWII was saved by vast amounts of lend-lease supplies from its capitalist allies, who were fighting a global war against two enemies, while Russia battled only on the Eastern front. The Russian army was - and is - incompetently led, utterly corrupt and cruelly indifferent to the lives of its soldiers. Putin's failure in Ukraine reflects his and Russian citizens' refusal to learn those lessons. JL

0 comments:

Post a Comment